A reluctance to work or an unwillingness to go forward, difficulty collecting, abnormal canter transitions or an inability to sustain a normal canter, unresolved hindlimb lameness, stiffness, and muscle pain. All somewhat vague symptoms that could be attributed to several causes – including MFM.

A different disease to MFM in humans and generally much less severe, MFM in horses has to date only been identified in Warmbloods and endurance Arabians, and likely represents an interaction between the environment, a complex number of genes, and diet.

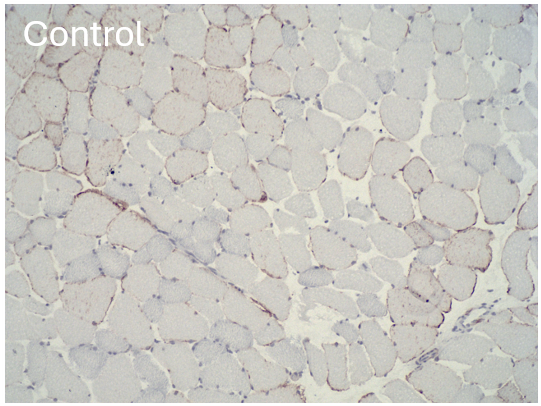

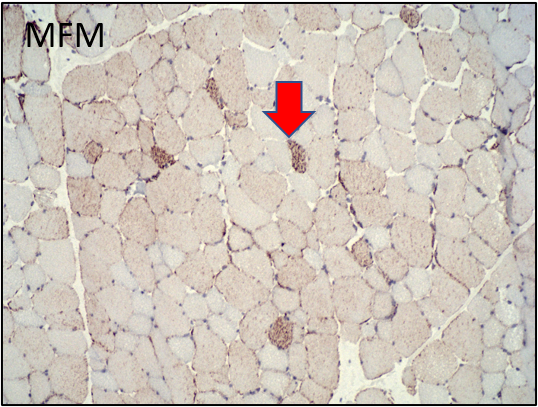

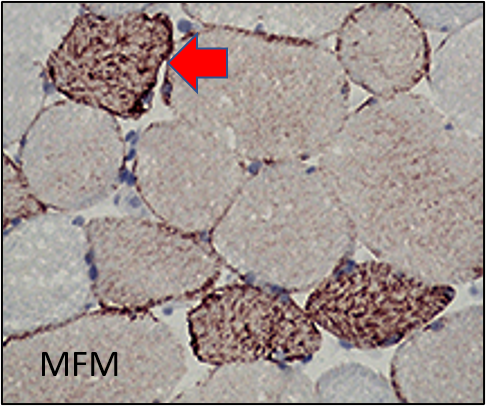

“It is defined by a specific microscopic change in muscle samples known as ‘desmin aggregation’,” explains Dr Peter Huntington (BVSc (Hons) MANZCVSc), Director of Nutrition at Kentucky Equine Research (KER).

“In Warmblood horses, MFM appears to be a later stage of what we once called type 2 polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM2). MFM horses were previously diagnosed with PSSM2 because they had small clumps of glycogen – the storage form of sugar in muscle – in their muscle.

“Recent biochemical analysis of muscle from PSSM2 Warmbloods found that the concentrations of glycogen are normal, and not excessively high like type 1 PSSM – indicating that PSSM2 in Warmbloods is not a glycogen storage disease.

“Further research found that scattered fast-twitch oxidative muscle fibres have abnormal aggregates of a cytoskeletal protein called ‘desmin’, Z disc disruption, and disorganised alignment of contractile proteins (myofibrils). The desmin aggregates seem to reflect oxidative damage in the muscle.”

MFM has also been identified in endurance Arabians, and likely represents an interaction between the environment, a complex number of genes, and diet.

How do I know if my horse has MFM?

As Dr Huntington explains, symptoms of MFM often develop gradually and vary between Warmbloods and Arabians.

When it comes to Arabians, particularly those competing in endurance, Dr Huntington explains that the most common clinical sign of MFM is intermittent tying up – which presents as episodes of muscle pain, stiffness, and reluctance to move.

“Metabolising large amounts of free fatty acids at the end of endurance rides without enough cysteine-based antioxidants results in oxidative stress and then muscle damage.

“The severity of muscle stiffness can be much milder than that seen with classic tying-up. For example, horses may appear slightly stiff and have dark urine without being completely unwilling to move after an endurance ride, or if horses have been rested for a few weeks, marked muscle stiffness often occurs approximately eight kilometres into a light ride. Increased serum creatine kinase (CK) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels can occur but may not be as high as in classic forms of tying-up.”

Dr Huntington explains that MFM is more complex in Warmbloods, with desmin aggregates occurring due to loss of the amino acid cysteine, oxidative stress, and also a maladaptive training response.

“The signs are pain and reluctance to work, without rhabdomyolysis – that is, the breakdown of skeletal muscle. Affected Warmblood horses often have a normal training response initially, but gradually develop exercise intolerance by six to eight years of age. They show a lack of stamina, unwillingness to go forward, an inability to collect, abnormal canter transitions, and an inability to sustain a normal canter.

“MFM horses may also show unresolved hindlimb lameness, stiffness, muscle pain and, rarely, an episode of exertional rhabdomyolysis with high serum muscle enzymes CK and AST indicative of muscle cell damage. However, in most MFM horses, serum CK and AST activities are within normal limits.”

It has also been found that MFM horses also have a high incidence of gastric ulcers.

While MFM has only been identified in Warmbloods and Arabs to date, it’s believed to likely exist in other breeds and Dr Huntington says that several horses of varying breeds with chronic muscle stiffness have responded positively to treatment.

Early diagnosis is important

When it come to MFM, early diagnosis is important. “MFM is debilitating to performance, and the stiffness could reflect a degree of pain,” notes Dr Huntington.

When diagnosing the condition, it’s crucial to first eliminate other potential causes of exercise intolerance, such as saddle fit, lack of fitness, painful hocks, sore back, and sacroiliac issues.

“Many muscle disorders have a genetic basis and can be diagnosed by a genetic test – such as PSSM1 – but this is not the case with PSSM2 or MFM, despite what some commercial laboratories might say!” explains Dr Huntington.

“You either need a positive response to a treatment trial or a muscle biopsy. As the muscle biopsy can now be performed with a needle biopsy probe, the horse can go back to work the next day. If you take the biopsy after starting treatment it may lead to a false negative result.”

A combined approach to treatment

Managing MFM requires a combination of an exercise regime, diet and supplementation.

“In terms of diet, rations should focus on providing quality protein and specific amino acids to aid in making the proteins necessary to rebuild the contractile proteins (proteins that cause muscle fibres to contract). Additionally, since oxidative stress is likely to be involved in the degenerative process, antioxidants or precursors of antioxidants are important to support the mitochondria.

“There is no evidence that extremely low non-structural carbohydrate (NSC), high-fat diets often fed to horses that tie up are needed by Warmbloods with MFM,” continues Dr Huntington. “There does not appear to be a scientific reason why additional fat – a potential source of oxidative stress – would be of benefit. Warmbloods are typically fed fairly low levels of concentrate with lower protein and NSC levels and higher fat contents, and these feeds may aggravate the condition. This type of diet may not have sufficient amino acids such as lysine, methionine, and threonine needed for muscle repair and the generation of cysteine-based antioxidants.”

Therefore, concentrates for MFM horses should include higher levels of protein (12-16% crude protein) containing high-quality amino acids; moderate levels of NSC (20-30%); and fat (4-6%). Feeds for Arabs could contain up to 8% fat.

Dr Huntington explains that for good doers or easy keepers, a ration balancer pellet that contains protein, vitamins, minerals – such as KER All-Phase pellet – may suffice. For horses that need extra energy, a feed such as Barastoc KER Low GI Cube is suitable and has been used as part of successful feed programs for horses with MFM.

Amino acids and antioxidants should also be added to the diet, and whey-based proteins are often recommended because they are rich in cysteine. Dr Huntington recommends working with a nutritionist to determine whether additional amino acids are required depending on the concentrate you are feeding.

“Horses with MFM have decreased expression of mitochondrial proteins and antioxidants in their muscle. Coenzyme Q10 is a key component of the first step in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Arabian and Warmblood horses with MFM have decreased expression of proteins involved in this first step – and so Nano-Q10 can assist with this.

“With any case of muscle atrophy, we like to ensure horses have normal serum and muscle vitamin E levels; in the US they can measure serum vitamin E, and then commonly supplement with Nano-E if required. However equine vitamin E assays aren’t available commercially here so a course of supplementation is usually warranted.”

MFM Pellet

In 2020, Professor Stephanie Valberg (DVM PhD) and KER developed a supplement specifically for MFM horses. MFM Pellet was released in Australia in 2023 and is a supplement that contains high levels of amino acids, including the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) leucine, isoleucine, and valine to promote muscle strength and development – as well as a special form of the amino acid cysteine that is readily absorbed in horses.

“Cysteine is a key component of many antioxidants, particularly those that are low in MFM horses,” explains Dr Huntington. “Leucine and other BCAAs stimulate protein synthesis in the muscle post-exercise, which is beneficial to MFM horses. Dr Valberg’s research shows this supplement is the best means to treat horses with MFM when combined with feed and exercise changes.”

MFM pellet is available from veterinarians. Research has shown that horses with MFM typically take four to six weeks to respond to changes in exercise, diet and supplementation.

For more information, talk to your vet or head to www.Equinews.com and search ‘MFM’.

This article was written in conjunction with KER.