Tucking our horses away in a warm, enclosed barn on a cold winter’s day makes us feel good, but is it what our horses really want? Equitecture founder Anthony Worm has spent more than 20 years working in the field of equine architecture, and he believes we need to approach it from the horse’s perspective.

“Horses haven’t evolved around buildings; that’s a human thing,” says Anthony Worm. “We’re so used to having buildings around us all the time. As an architect, I understand that intimately: a secure, closed in structure is an innate need for people, and I think we extend that need to our horses. Their optimal form of shelter is different to ours.”

To put a horse in a closed-in stable, for example, may feel like the right thing to do by the horse but in actual fact horses have their own evolutionary needs – and while shelter is one of them, a traditional stable is not. “Buildings aren’t really a good fit for horses, unless they’re designed well,” he continues.

Horses did not evolve around buildings, and we need to keep that in mind when designing equine architecture.

With a passion for research and through lecturing at university, Anthony explains how over the years he developed an interest in the history of equestrian buildings – in particular stables and how their use came about.

“For the predominant part of the last 6000 years, horses have been used by humans for war; they have been a war machine. Some of the earliest recorded stables were built to keep horses ready for war. Horses were kept in stables and the handlers or riders/soldiers often slept with the horses. Some of the earliest discovered permanent stables were in ancient Egypt, about 3200 years ago, so it’s a very old building practice,” he explains.

“Some of the earliest discovered

permanent stables were in ancient

Egypt, about 3200 years ago…”

“In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that all changed. Horses stopped being used for war. They also stopped being used for transport and labour, and today they are predominantly used for recreation purposes. I do believe stables, in their traditional form, are very much past their use-by date. One must ask whether they are even necessary anymore.” If we are still going to build stables, Anthony says it’s of critical importance to approach the project with a horse-centric viewpoint.

In 2001, Anthony was involved in designing racing stables for the Freedman brothers at St Andrews Beach. Image supplied by Anthony Worm – Equitecture.

Anthony founded Equitecture in 2010, however his practice had designed buildings for equine purposes previously in his work as an architect. It was in 2001 that the practice took on its first equine-related job, designing racing stables for the Freedman brothers.

“At the time, the Freedmans were particularly interested in open courtyards with stables that had great ventilation while also minimising strong coastal winds,” he explains of the buildings designed for their Mornington Peninsula property. Those stables are these days the home of St Andrews Beach Brewery, a popular venue that has since won architectural awards.

“We aim to incorporate scientific

evidence that will ultimately lead

to much better welfare outcomes.”

The Freedmans were particularly interested in open courtyards with stables that had great ventilation while also minimising strong coastal winds. Image supplied by Anthony Worm/Equitecture.

Since making equine architecture his primary focus, Anthony has thought more deeply about equine buildings – particularly stables – and how they can be designed with the horse at front of mind.

“We aim to incorporate scientific evidence – from equine evolutionary, zoological and behavioural aspects – that will ultimately lead to much better welfare outcomes for the horses, and in turn achieve much better outcomes for the owners of the horses.

“Good design must accommodate the functional needs of the facility as well as incorporating the needs of the horses, so it is quite a complex balance of competing needs.”

So, how exactly do we make sure our equestrian buildings are horse-centric?

GOOD VENTILATION & INSULATION

Anthony says fully enclosed barns without insulation are one of the most common types of stabling he sees – and he says they’re one of the biggest design mistakes for our horses.

“Allowing good air changes through stables – and equine facilities generally – helps prevent dust and pathogen build-up. Dusty stables affect horses’ lungs… they develop lower airway disorder really easily and it’s a difficult disease to scope for because it often doesn’t present any symptoms in the beginning,” he notes.

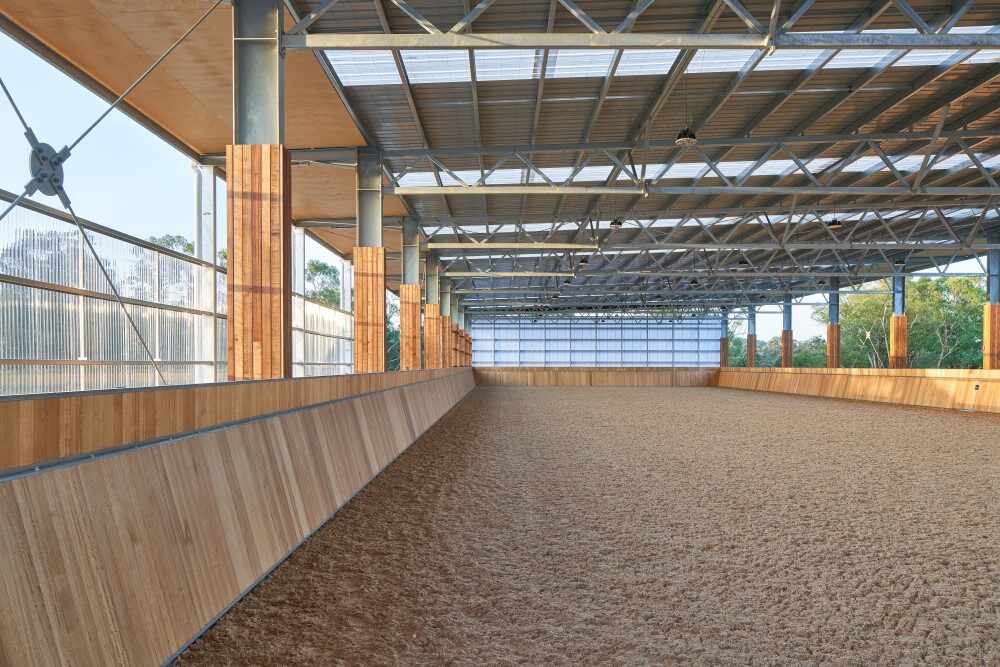

Allowing good air changes through equine facilities helps prevent dust and pathogen build-up. Image of Helmast Park, supplied by Anthony Worm/Equitecture.

The way ventilation is designed of course depends on the local climate. “You want to get the right kind of ventilation, as blustery conditions are no good either. Horses rely on their hearing, so if it’s very windy that makes them anxious as it affects that. Being able to limit gusts through a facility is important.”

Of course, while you want to reduce wind, there still needs to be air movement. Typically, Anthony will design stables – and also ‘indoor’ arenas and other equestrian buildings – with walls that don’t extend all the way to the roof, as this facilitates ventilation. “We create the air movement above a horse’s head near the roof so any wind doesn’t affect them. At the same time, that also has the dual effect of ventilating heat away from where it often builds up, near roofs.”

With many parts of Australia having quite a warm climate, heat build-up is a very real concern that needs to be considered.

“This is also why we

absolutely refuse to

design closed-in sheds!”

Equitecture designs buildings to facilitate air movement above a horse’s head near the roof, so any wind doesn’t affect them. Image of Helmast Park, supplied by Anthony Worm/Equitecture.

“There was a study released that discussed the notion that horses [depending on the breed] don’t need to expend a great deal of energy between 5°C and 25°C [a horse’s thermoneutral zone] to actually maintain a comfortable body temperature,” explains Anthony. Conversely, humans have a much narrower and warmer TMZ – typically feeling the cold before a horse would.

“It actually has to be relatively cold for horses to be affected. Conversely, anything above 25°C and horses start to get hot and need to cool down. In Australia that’s actually very easy to exceed, particularly in a tin shed with no insulation. We always insulate and we always try to keep the facility as open as much as possible to allow good air change, as that wicks heat away and helps to prevent it from radiating down into the facility. This is also why we absolutely refuse to design closed-in sheds!”

SAFETY FIRST

Every horse owner knows that safety is an important consideration when it comes to horses, and Anthony takes several key elements into account. “Stable and building fittings must be robust to limit damage from equine residents. We predominantly design rubber-lined stables now, because we’ve found a good product in conveyor rubber; it’s an easy product to keep clean and it’s very durable and strong. Horses can kick it without any damage, and we fix that to a steel frame in a special way so way that horses cannot get to the edges and pull it off.”

Equitecture often uses conveyor rubber in stables and other areas, as it’s very durable, strong and easy to keep clean. Image of Helmast Park, supplied by Anthony Worm/Equitecture.

Anthony says that by using steel frames and fitouts rather than timber it minimises maintenance over time and ultimately leads to a safer environment. “Timber stables can get kicked and splinter, urine rots wood… that affects health as well. It not only affects the longevity of the stable, but as materials break down, nails come loose and pose an injury risk for horses.

“The screw fixings that we use are also very minimal and sit flush, so there is no real chance of them dislodging. Sliding or swing doors on stables, we incorporate hinges and latches into the line of the door as much as possible. External latches, if left open, they can catch on things and damage not only equipment but also the horses themselves.”

LET THERE BE LIGHT

“There was a study published about horses’ eyes… they take a long time to adjust to changes in light conditions compared to humans,” notes Anthony. “Therefore, if they’re walked into a dark facility they can’t actually see for a period of time, perhaps half an hour. Human eyes can adjust really quickly; people forget that animals might have particular differences in their evolutionary makeup than what we have.”

Taking horses’ eyesight into consideration, it’s optimal to incorporate a lot of natural daylight in stables and other equine buildings so they are not too dark during the day. “North-facing orientation is really important as it allows us to get direct sun into stables and other buildings. This is not only better for the horses coming in from outside, but the UV acts as a way of minimising pathogens and keeps things dry. Stables can be quite wet places at times, whether that’s water buckets, a wash bay or just hosing the facility down to keep it clean, there’s always a lot of water involved!”

Allowing light into equestrian facilities is important. In the case of riding arenas, even light without direct sun is preferred so you don’t get glare or shadows across your riding surface. Image of Helmast Park, supplied by Anthony Worm/Equitecture.

Anthony caveats access to sunlight in acknowledging the fact that there are situations where you may not want too much direct sun. “For instance, in arenas, even light without direct sun is preferred so you don’t get glare or shadows across your riding surface or harsh sun conditions where you can’t see properly.”

AGENCY & SOCIAL ASPECTS

“Giving horses agency is a big thing,” says Anthony. He explains that another mistake sometimes made in equine building design is creating a layout that isolates horses and doesn’t give them the ability to interact with others; this may then lead to them developing stereotypies.

“Good stable and equine building design should promote agency to make decisions about when horses want to drink, when they want to feed. We’re also optimising the ability for horses to interact with other horses in the way the buildings are designed. Having a line of sight to other horses in paddocks and other parts of the property, even if they can’t have direct contact with them, is important.”

BETTER FOR HORSES, BETTER FOR HUMANS

“Ensuring the way in which stables and equine buildings are designed are horse-centric promotes a way of a management for the owners where the horses’ maintenance is actually quite minimal. Ultimately, the horses end up much calmer and much easier to handle because they’re a lot more comfortable,” says Anthony of how designing with horses in mind also helps humans.

Ensuring stables and equine buildings are designed to be horse-centric promotes a way of a management for the owners where the horses’ maintenance is actually minimised. Image of Helmast Park, supplied by Anthony Worm/Equitecture.

“It has a massive

impact on horses.”

“Horses that are managed with their innate needs in mind are less likely to have behavioural issues as a result of being uncomfortable or too anxious, and in turn they handle and perform better. The Freedmans always used to say their horses ate 20% more food while at the St Andrews Beach facility than anywhere else they’d trained from previously – from a racehorse perspective where horses are often finnicky eaters, that’s a very positive outcome.”

WELFARE CONSIDERATIONS

There are of course important reasons why a property may need several stables handy, and as such Anthony finds they are still a common feature in Equitecture’s building plans. Stables can be a useful way to keep a horse at hand and out of the weather for vets and farriers and can become a necessity in the rehabilitation of injuries and ailments.

However, from Anthony’s perspective the use of stables should be minimised – and certainly not used as a regular part of a horse’s day-to-day existence – if we’re serious about equine welfare.

“The practice of putting horses in buildings really does constrain a lot of their evolutionary needs,” says Anthony. “Horses are built to move. When grazing, for example, one study showed feral horses typically cover around 17km per day over about 12-16 hours, centred around a water source; domestic horses is less, but still up to around 7.5km. They can’t do that in a stable.”

Anthony finds it interesting that the industry focuses on a range of practices under the welfare banner such as nutritional needs, veterinary procedures and training practices, however facility design garners less attention. “That’s despite the fact it has a massive impact on horses. It not only affects how they’re managed, but how the horses feel themselves. That is often overlooked in the industry.”

Anthony says that although stables will be here to stay for a while yet, he has noticed changes over the past 20 years. “Having specific stable boxes for each horse is slowly being reduced as a primary requirement, and now the bulk of the structure is more to do with all the functions that are around keeping the horses – such as indoor riding arenas, wash bays, tack rooms and feed rooms – but not necessarily the stables themselves.”

Anthony has noticed a shift away from buildings that provide a stable for every horse; instead, the structures Equitecture is designing are more focused on accommodating the functions around keeping the horses – such as riding arenas, wash bays, tack rooms and feed rooms. Image of Helmast Park, supplied by Anthony Worm/Equitecture.

Some believe that their horses love being in a stable and prefer it to their field, but Anthony would argue that this is a learned behaviour.

“Horses are highly trainable animals. That’s why they seem quite settled and comfortable in facilities they are used to. That’s why they will float without a problem… that’s why you can train a horse to monitor a riot in the middle of the city.”

“If we were following a welfare-based design logic to conclusion, we’d have no buildings for horses,” muses Anthony. “Ending the use of stables as part of a horse’s day-to-day housing is going to be a long, long way into the future; it’s just little baby steps. It’s an endeavour of practice obviously, but also an endeavour of education. In the meantime, let’s make our stables as horse-centric as possible.” EQ

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE TO READ:

From Dreams to Reality – Equestrian Life, May 2024