It’s 50 years since Gail Ritchie and her mare Clover Kamali made the long trip from Tasmania to Moonbi, New South Wales, to contest Australia’s first NCHA Cutting Futurity. Emerging as Co-Champion that year, Gail later became the 1983 Futurity Champion riding Clover Honky Tonk, another mare bred by her family’s stud. Remarkably, she remains the only person to have won the Open and Non-Pro Futurity titles on the same horse – and the only woman to claim the Open Futurity title – in the event’s history.

Gail Ritchie hails from an era and family of great horse people. Her father, Gregory Lougher, was a Californian cowboy who rode broncs, cutters, cowhorses, hunters, jumpers and just about everything else. Starting his stud Clover Leaf with the mare Kamappeal when he returned to the United States after World War Two, he emigrated to Australia in the 1960s with 31 horses on a boat, a story Gail tells in his biography “A Good Hand”. Included in this shipment were the first cutting horses to reach Australia, with Clover Leaf Stud re-established at Murrurundi in NSW.

Gail grew up in the saddle, pictured here as a child in America.

“Clover Kamali was born in 1970 at Clover Leaf Stud and she was a chunky, gorgeous, bossy little foal,” Gail recalls with a smile, as she reflects on the early life of her future champion. “Her mother, Clover Lori, was the dominant mare of the whole band, and when she would walk up, the sea would part! So Kam learned that at an early age from her mother. She was never cranky, she just expected everybody to get out of the way!”

The precocious youngster was started lightly under saddle in NSW before moving to Woolnorth, Tasmania as a two-year-old with Gail when she married Blyth Ritchie. Being the first foal out of Clover Lori, and by Jack Hammer – both horses that Gail’s father had brought on the boat from America in 1967 and outstanding performance horses in their own right – she was an obvious horse for the family stud to keep rather than sell.

Jack Hammer, sire of Clover Kamali, with Gail’s father Gregory Lougher.

Clover Lori, dam of Clover Kamali, competing in Reined Cowhorse with Gail.

“I had never actually trained a

cutting horse before Kam.”

“She was a lovely cutting horse type, and the fourth generation of the first mares that my father owned; it’s a line we still carry on to this day,” Gail explains. “Bonny Young broke her in before she came to Woolnorth with me, and she didn’t take much to get started, she was smart as she was calm, she was just easy.”

Kam may have been easy to ride, yet Gail was just 22 years old and despite having grown up in the saddle – riding and competing in almost every discipline imaginable – she lacked experience in the task that lay ahead of her.

“I had never actually trained a cutting horse before Kam. I’d ridden a few of Dad’s but I’d never trained one from the start, so between Kam and I we worked it out. She probably was a bit smarter than me!” Gail explains with a laugh. “Any showing of cutting horses I’d done was as a kid in the States, but I knew how a cutting horse should feel, so I just went off what I felt the horse was supposed to do. I rode Kam in a hackamore because she was not terribly light in the mouth; she wasn’t all that good in the snaffle but she was as light as a feather in the hackamore.

EXPOSED TO MUSTERING

“Being on a large property like Woolnorth, she was exposed to a lot of mustering and during her training she never saw a stale cow because there were 5,000 head of Herefords on Woolnorth and every day we brought in fresh cattle for her,” Gail explains. “I’ll never ever forget when we first brought a mob in; she hadn’t yet worked cattle in the pen, she had just been mustering at this stage. We had these beautiful weaner heifers that were going be sold, and Blyth said, ‘Well you can just work these before they go.’ Back then there was no trailing cattle around the round yard, or mechanical cows before you worked cattle on a young horse; we did not know what she’d do!

“I rode into the mob to cut one out, and the cow ran down to the end, then came walking back towards us. I rode out there on Kam, and she dropped down then drew back and her two front feet started tapping away, and she was snorting at the cow, and when it moved she went with it. I’ll never ever forget that, she was just a natural!” Gail reminisces.

The decision was made to travel to the mainland for the first NCHA Futurity when Kam was a three-year-old. In the current era, nominations for the NCHA Futurity are submitted around eight months before the event; this wasn’t the case for the very first NCHA Futurity, however it was still a huge decision and commitment to enter a major event so far from home.

Gail and Clover Kamali showing at a later event; note the thin cutting pen surface!

“We did have to nominate, and make one or two payments, but nothing like as much as they do now. There had already been some classes named Futurities held in Australia before 1974, but they weren’t truly Futurity classes,” Gail explains. “The Futurity at Moonbi was the first one that ruled the horse had to be a three-year-old and it could not be shown before the event. It was actually run by the New England Quarter Horse Association; they built an arena especially for cutting and rodeo events. The Wilson brothers were very much involved; they organised the event and tried to run it as much as possible like the American Futurity. They arranged Bubba Cascio to come out from the States to judge, but the event was run as an aggregate at that time, rather than go rounds and a clean slate final as it is now.”

Gail recalls being happy with how Clover Kamali was working at home at Woolnorth, and feeling that they were ready to go and show! A plan was made to head to Murrurundi en route to Moonbi, and get some help from her father and some final work on cattle before the Futurity. Gail starts to laugh as she recalls how the lead-up to the event didn’t quite go to plan.

“Blyth set off with Kam from Woolnorth to Burnie in his Landcruiser and the heavy old Rice float. They went on the ship, and I flew over and met them on the docks at Melbourne,” Gail recalls. “Between Melbourne and Murrurundi we had four flat tyres! I remember we stopped at Forbes and had to order new tyres for the trailer, and wait for them to arrive, so it took us longer to get to Murrurundi than the two days we thought it was going to be.

“We finally got to Clover Leaf and it was pouring rain, Kam had not seen a cow for days, and at Murrurundi there was no sand arena, we just had that lovely loamy dark soil that is usually great but was like a gluepot after the rain and I couldn’t work Kam in there,” Gail explains. “All I could do was ride her around the paddock! Working cattle was an impossibility, so I didn’t have that last-minute tune-up and work on cattle that I had counted on.”

Gail competing on Clover Kamali.

A modern-day Futurity horse can be worked in the practise pen at a show, and be schooled using a mechanical cow, however these were yet to be invented in 1974. Furthermore, cattle are now extensively “settled” at the start of a class for around 30 minutes and riders hope to draw early in the class, meaning they can choose well-settled cattle that will complement their horse’s style. Fifty years ago, an early draw was not desirable – cattle were barely settled and were often flighty and precarious for the first few riders.

‘COULD ANYTHING MORE GO WRONG!’

“We got up at around 5am and headed to Moonbi; when I arrived I found I had drawn No. 1 out! I thought, ‘Oh could anything more go wrong!’” Gail laughs. “I’d drawn first out, my mare hadn’t seen a cow in over a week, there was no practise pen, no mechanical cow, it was just a case of lope your horse, do what you can do, and go in.

“So in I went, and because she hadn’t seen a cow for a while, in our first cut I kind of had to hold her up a little bit because she wanted to do all of her boogie-woogie moves,” Gail explains. “I picked up on one end, she was getting a little loose, so I scored a 69 and I thought, ‘Well that’s fair enough’.

“I wasn’t expecting much, I really wasn’t,” Gail continues. “Max McTaggart and Chilla Seeney, Wally Leeson, Robert Baldwin, all of those guys were in the class and they were supposed to be these big heroes; well, they didn’t fare as well as me! They were getting scores like 65, 64, 63, so I was actually sitting in a pretty good spot. Everybody was worse than me except for Paul Luckie, he came out and he got a good score of 71 or something like that, and he looked sharp.

“The following day in the second go round Kam really tightened herself up, just from finally seeing a cow, and she worked really well. I had relaxed a bit more, had a better draw and could do a bit more in the pen. I can’t remember what the score was, 70 something? Once again, all those heroes didn’t do as well as I thought they were going to do. Kam was just a real cow horse, and I do think that a lot of the other horses were a little loose, rolling through their turns rather than stopping and drawing like she did.

“Paul Luckie had spent time riding cutting horses in America and his horse, Garswood Red Flash, looked really good, but they didn’t go quite as well as they did the first day,” Gail continues. “So then we went into the final which was really the third round of the aggregate, and lo and behold, I had another fair run, and Paul did too, and when they added up the scores we tied! I thought Paul’s horse looked good and that he would win so I wasn’t expecting it, I was just happy that we had done what we did with such a botched preparation – it was a lot of fun to find out that Kam and I had tied for the win!”

The 1974 NCHA Futurity trophy takes pride of place in Gail’s home.

Fifty years may have passed, yet Gail is right there in the moment as she talks about how her mare worked that week. She doesn’t dwell on how immense the achievement was; nor comment on the fact that she cut quite a different figure to the rest of the field as a woman in her early 20s, riding the very first cutting horse she had trained in a remote location many miles from home.

“I can’t remember if there were any other women competing that year,” Gail muses, when asked if she was the sole female in the field of around 20 entrants. “No, I think I was the only woman. We were all just competitors, it didn’t matter. Competing against men, you’re no better and you’re no worse off, you’re just another competitor.”

Of greater poignance than gender is the memory of the rare compliment Gail received from her father after he watched her compete.

“The Prayter family brought Dad up to watch me, it was not too long after his life-changing accident and he couldn’t do much. After the first day he came up to me and said, “Good job daughter, the only thing I’d change is my horse would probably be a little bit cowier,” Gail recalls. “He also said, “I don’t think I could have done better myself.” Dad wasn’t one to rave about things; that was a big compliment from him!”

After her Futurity year, Clover Kamali went on to win the Maturity class – an event for four-year-olds, now known as a Derby – at the AQHA Q75 show, and several Open Cuttings including the Gold Cup before retiring to the breeding barn, having done and won everything she could in the show pen. Clover Kamali produced 15 foals, with most of them having prolific show careers themselves, including champion cutting horses Oaks Midnight Oil, Clover Captain Cook, Lipstick N Lace and Clover Cazaly, along with Clover Rambo Morn, who was a legendary barrel racer and held the Australian record for many years.

After retiring from her cutting career, Clover Kamali went on to produce 15 foals!

NINE YEARS BETWEEN APPEARANCES

Nine years passed before Gail’s next appearance at an NCHA Futurity, riding Clover Honky Tonk. ‘Honk’ was a roan mare by Easter Chex, a stallion Clover Leaf had imported from America and out of Clover Wacadoo – who shared the same sire as Clover Kamali, Jack Hammer. By 1983 Gail and Blyth had two sons, Brett and Rafe, and the family had moved from Tasmania to Mountain Creek in New South Wales. Unlike most Open Futurity winners, Gail was not a professional rider; as such, competing at the NCHA Futurity was something she only felt compelled to do when the right horse came along, rather than aiming several horses for the event each and every year.

“David Costello was working for Clover Leaf in the early 80s and he didn’t like Honky; he broke her in and said she wasn’t that good, so I took her on,” Gail explains. “Like Clover Kamali, she had a big ticker, she was easy to train, naturally had a good stop, and just wanted to work a cow. Kam was a bigger, stretchier mare with a bit more range and move – I truly believe Kam would have been competitive today – and ‘Honk’ had so much try and never made a mistake, so we entered her in the 1983 Futurity in both the Open and Non-Pro divisions.”

In 1983, the NCHA Futurity was held at Kooralbyn in Southern Queensland. Once again, it was a long trip for Gail – this time, with two young sons in tow – and once again, the skies opened and the rain poured down.

Clover Honky Tonk had a lovely temperament, ridden here by Gail’s son Rafe Ritchie, both pictured aged three!

“It started raining the night before the show was due to start. At Kooralbyn, to get to the arena from where we were all staying you had to go down a causeway and cross a creek. After several inches of rain, the creek became a torrent, it was over the banks and spreading,” Gail recalls. “There was no getting across to the rodeo arena, where we would be showing, so we had to sit and wait it out. We sat there for two full days and on the third day it was still too high to get across!

“Of course, we all had an absolute ball camped up there, everyone had fun, but we couldn’t really ride our horses. We tried to but all we could really do was trot them up and down the roads, everything else was flooded. Even in their stalls the horses were standing in muck. Eventually the show got underway, but none of the horses had had any prep, and the arena was sanded but there was water all over it, so when you stopped your horse, water sprayed everywhere and we were covered in it when we rode, it was unbelievable.

“At that particular show they decided that we would follow the same format as the United States, so we had to have two go rounds, a semi-final and a final in the Open Futurity. The Non-Pro only had two go rounds and a final. So if Honk was to make both finals she would have seven runs over three or four days; no practise pen, no mechanical cow, just warm up and go in,” Gail explains.

“The interesting thing about Honk’s preparation was that we’d had a big season at home; a really good autumn after a dry summer and spring, and we had a lot of clover come through, which meant serious calf growth and we were pulling calves left, right and centre,” Gail continues. “I had to go out twice a day and check the heifers to see which ones we were bringing in to calve down. Rather than bringing them all in, Blyth said it was good training for my cutting horse to bring in the ones that had calves hanging out the back of them. So Honky had to cut out and drive out cattle by herself; she was so cow smart and she had done all of this in conditions that were slippery and tough. When I took her into that pen at Kooralbyn, slipping all over the place, she just thought, ‘Oh here we go, another heifer, I’ve got a job to do! I’ve got to hold my line!’ And she went across there and did her thing. She was so cowy and she would put her little head down and do all these cute things. You couldn’t do much in there because it was so slippery and you had to hold your feet. But she never felt unstable because she was used to working a cow in tough conditions, and not overdoing it.

“A lot of other horses in the class were penalised for having misses and things like that because they weren’t sure of the ground. So I was just poking along there getting my 71s, 72, scores like that in my go rounds,” Gail explains. “We got through to the Open final and just like in 1974 I drew out No. 1 and thought, ‘Oh well, we made the final, I’ll have more of a chance in the Non-Pro, this is a great preparation for that’.

‘WE HAD WON THE OPEN FUTURITY’

“We went out there in the final and Honk was just so solid, it was still wet and sloppy but she was a cowy little thing and smart. She did nothing wrong; we couldn’t do a lot but she was accurate and I think she scored a 71 or 72, something like that, not a big flash score but a good score out first,” Gail continues. “I was sure someone else would get around us, but it turns out no one did! It was just unbelievable. We had won the Open Futurity!”

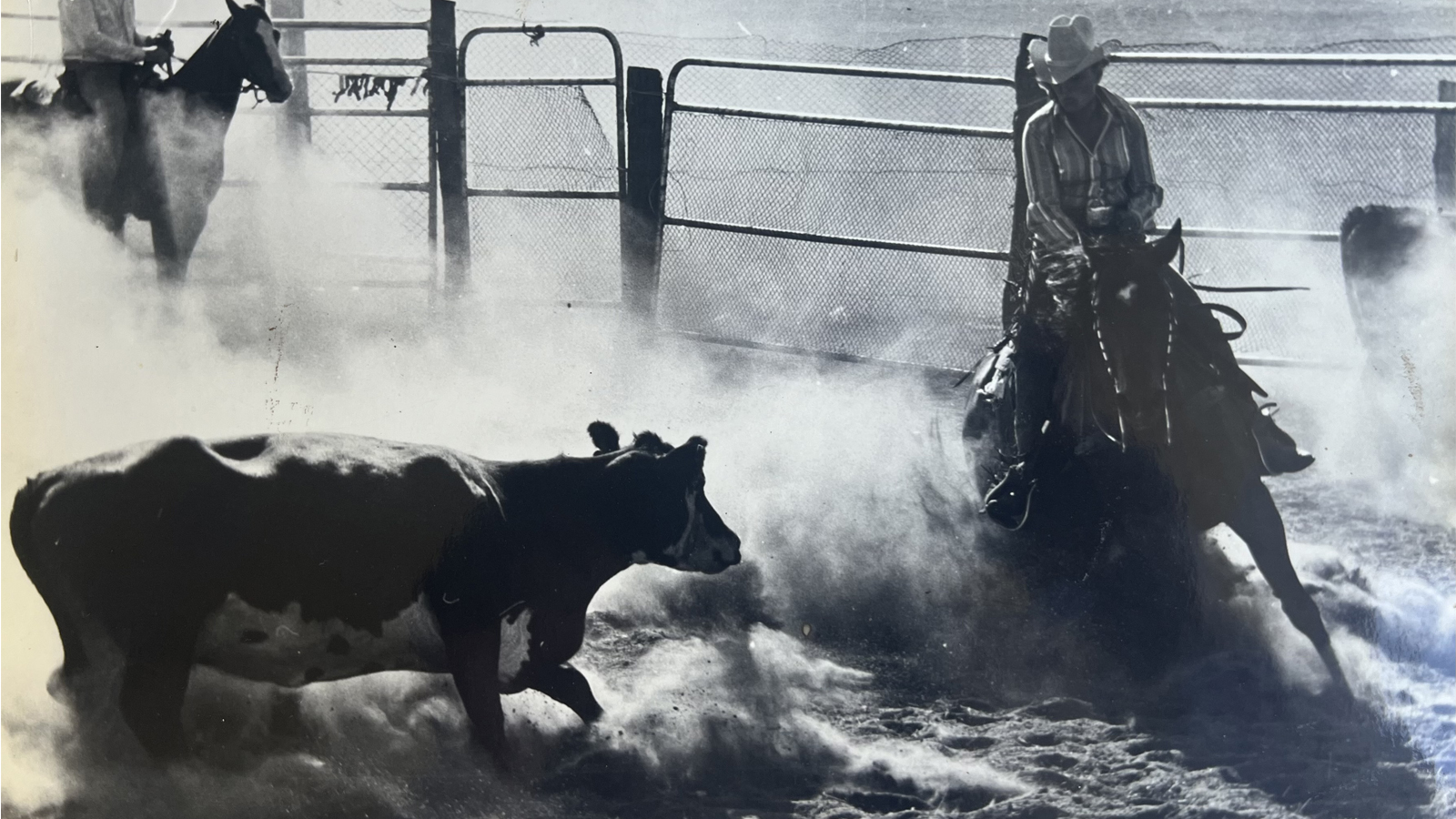

Clover Honky Tonk showing her grit in an incredibly wet pen to win the 1983 NCHA Futurity.

In 1983, the Futurity show did not run over two weeks as it does in the modern era with a schedule that allows horses rest days between finals. Gail recalls there were around 27 or so combinations in the Open Futurity Class, and the final for both the Open and Non-Pro divisions were held on the same day! Clover Honky Tonk, fresh from her win in the Open, returned to the pen and to Gail’s delight won the Non-Pro final too.

“Same day, same sort of run. We had those sort of yak cattle to work, and if you missed them by a little they would nail you and a lot of the horses were a little late with how they worked, and they got in trouble because of it,” Gail explains. “Honk was never late, in fact others always told me that I should send her outside a cow, but I said, ‘Not with these cattle!’ And we stayed tight, and won that Non-Pro class too!”

All smiles for Gail and Rafe Ritchie at the 1983 NCHA Futurity presentation.

Like Clover Kamali, Clover Honky Tonk continued to show after her Futurity win; in the same year she was crowned Futurity Champion at the Super Sires show and Non-Pro Futurity Champion at Moonbi, then returned to win the Non-Pro Derby the following year before retiring to stud and produced several good horses including Clover Cook Book, who won the 1994 Non-Pro Futurity with Gail’s sister, Lori Mackay.

Gail confesses that a preference for training and riding horses over showing them, and other commitments and interests limited the number of times she competed in the Open NCHA Futurity after 1983. Her strike rate of winning on two occasions from around five attempts is exceptional, more so when considering that Gail was a Non-Pro rider competing in Open divisions. While she no longer rides, Gail has remained involved in the sport of cutting, previously serving as both the general manager and president of the NCHA. Currently, Gail is assisting as a volunteer in preparation for the Champion of Champions event that will be held at this year’s NCHA Futurity in Tamworth on Friday, 7 June in celebration of 50 years of the Futurity. All past Open Futurity Champions have been invited to attend, with those still riding competing in the Champion of Champions class.

“I’m really looking forward to catching up with people I haven’t seen for years! There are some coming along that I haven’t seen for so long, so that will be fun,” Gail enthuses. “It’s always nice to acknowledge the horses too. There are some great horses that have been Futurity champions, horses like Docs Spinifex, that have gone on to have a profound impact on cutting in Australia. Then of course there are some really nice horses that have won the Futurity that people have forgotten about, and some really nice ones that didn’t win – but that’s cutting!” EQ

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE TO READ:

One Hell of a Ride in Heavenly Patagonia – Equestrian Life, April 2024