The diagnosis of kissing spines has been around for a very long time, but the significance paid to the condition has waxed and waned, with some blaming kissing spines on every back ailment and others believing it is over-diagnosed.

Kissing spines is the term given to the condition where the dorsal spinous processes in the spine are close to touching or overriding each other, causing back pain, especially when the rider mounts. It predominantly occurs in the thoracic vertebrae of the mid-back but has been reported in the lumbar vertebrae which form the caudal back.

There are typically 18 thoracic vertebrae (reports of 17 and 19 in some horses) in the spine and these start from the base of the neck (inside the shoulder region) and go to the lower back where the ribs end and the lumber vertebrae start. The thoracic vertebrae have long, upward projecting dorsal spinous processes compared to the other spinal vertebrae, with the longest thoracic ones forming the wither (T3- T10). The thoracic vertebral bodies are also modified to articulate with the head of the ribs, with most horses having 18 pairs of ribs.

The skeleton of a horse.

The reason a horse develops kissing spines is best described as multifactorial, meaning several factors combine to result in the spinous processes overriding and causing back pain. Poor conformation, hereditary predisposition, weak musculature/poor inner core strength, insufficient body conditioning or training, inappropriate saddle fit, poor rider ability/posture and trauma have all been implicated.

Poor conformation can be due to inferior genetics (hereditary predisposition) or issues that have compromised the normal development of the horse and resulted in the dorsal spinous process having a reduced space between consecutive vertebral spines.

VERTEBRAE LOSE STABILITY

The spine is stabilised by several different systems: the small muscles and ligaments that interlink one vertebrae with another, the larger group of back muscles that run on either side of the spine, a number of ligaments that run along the top of the spine from the head to the pelvis, and the abdominal muscles that are responsible for the horse’s inner core strength. When these muscles and ligaments are not strengthened appropriately, the vertebrae lose their stability and this can allow the spine to “sag”, effectively allowing the top spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae to come closer together and/or touch/override.

The thoraco-lumbar spine in its “normal” position is essentially a straight structure with equal distance between the dorsal spines dorsally (top) and vertebral bodies ventrally (bottom). The spine in this section can move laterally (sideways) as well as flex and extend, with less sideways movement in the lumbar spines. Whilst the thoracic vertebrae can flex and extend, the more common movement in the mid back is to flex, seen as a dipping motion particularly when the horse is stimulated along the mid back, or a saddle or rider is positioned.

This is different to the extension seen when the horse humps the lower back when something is run over the sacroiliac and sacrum (the hindquarter). When the horse flexes its back, the space between the vertebral bodies opens and the dorsal spinous processes come closer together.

The interspinous ligaments and muscles of the spine and abdomen in ideal circumstances support the spine and counteract forces that are placed on the back, to allow some movement of the vertebrae relative to each other to occur, but more importantly remain tight to ensure the spine comes back to its neutral position when the stimulus is removed. When the support muscles and ligaments are poorly conditioned or weakened through disuse, the spinous processes can fail to maintain their normal spacing and remain with a reduced space between them. If this continues to occur, the spines can slowly override, causing inflammatory and eventually degenerative changes to occur.

In cases where a saddle is not fitted correctly or a rider sits continuously in a poorly balanced manner, pain can cause the muscles in the back to be weakened over time, also allowing the spine to sag with a reduced ability to return to a neutral position. Kissing spines are not going to occur when a saddle is poorly fitted for a few weeks or a heavy/inexperienced rider lands inappropriately sometimes; instead it takes months to slowly form because it takes months of continuous insults to the supporting anatomical structures that maintain a healthy back for this to fail.

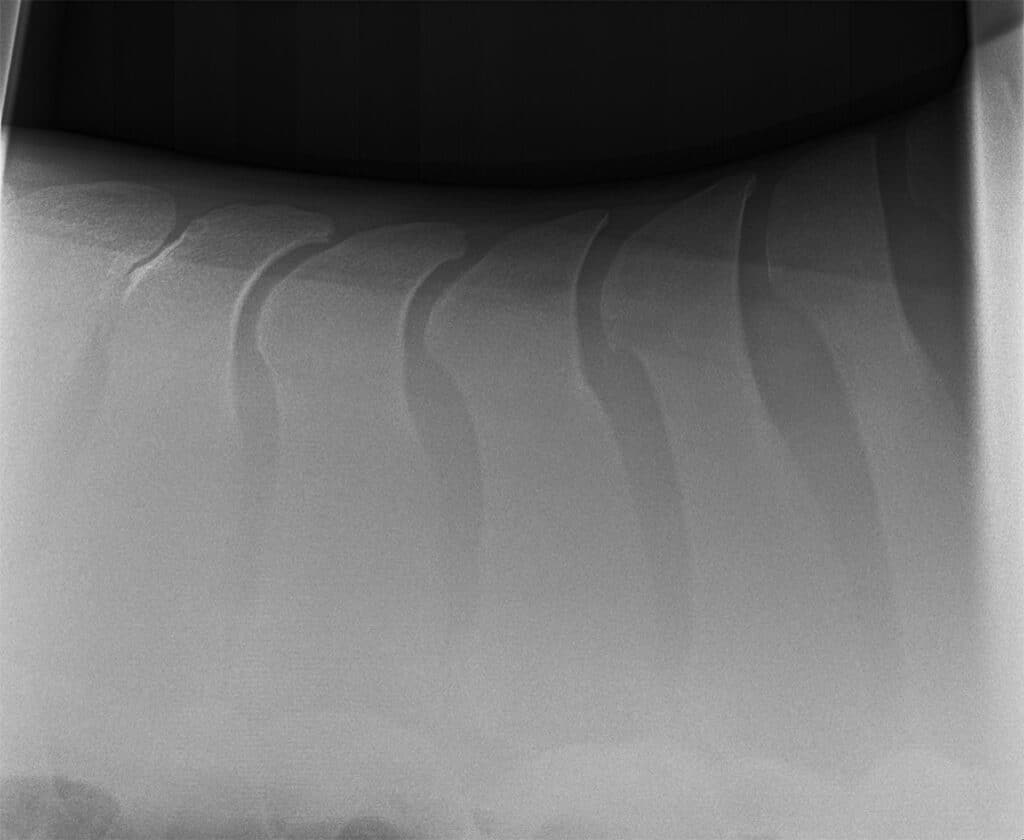

An X-ray showing both normal spacing of the spines, as well as kissing spines (left hand side) where the close dorsal spinous processes in between show some inflammation and degeneration occurring.

“There is a lot of debate

regarding the significance

of ‘kissing spines’.”

The back can also be examined using ultrasound along the tops of the spine to assess the space between them and exam the regularity (or irregularity) of the margins of the bone but is best used to assess the soft tissues around and between the spines.

To confirm if a horse has kissing spines that are affecting them, there are a few further tests that can be performed. A veterinarian can inject local anaesthesia into the area and monitor the horse for a response, normally a reduction in pain. Sometimes the vet will inject an anti-inflammatory medication into the area around the reduced space between the vertebrae and then assess the horse over the following weeks to look for a change in attitude or performance to confirm the kissing spines are affecting the horse.

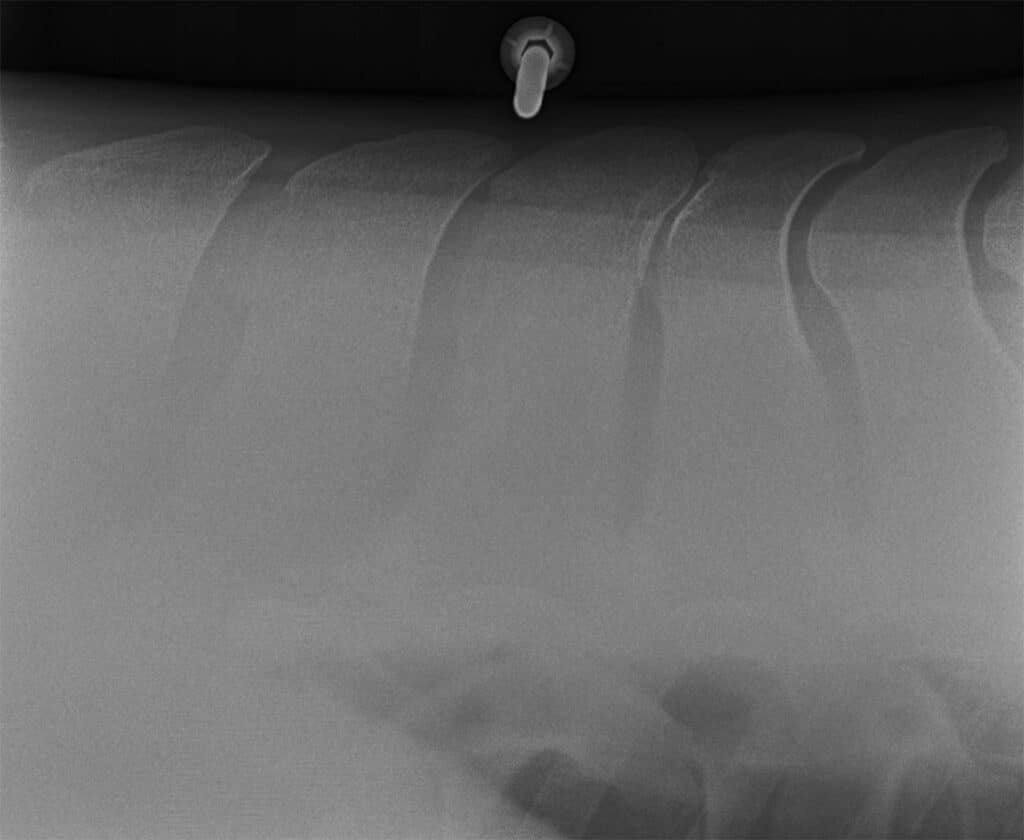

The same horse depicted in the previous X-ray, again showing kissing spines.

Scintigraphy can be used to fully assess the spine for “hot spots” or areas of bone that are inflamed or injured and probably gives the best indication of the significance of bony changes on X-ray. Whilst PET scans can highlight active inflammation in the bone, the scanning is limited to the knees, hocks and below, making the back inaccessible.

Treatment for kissing spines is varied and can include surgery procedures, medical therapies and conservative measures. Conservative treatment involves accredited saddle fits, a variety of saddle pads, exercises to promote inner core and back strength and using an array of chiropractors, physiotherapists, acupuncturists and Bowen therapists to alleviate the pain. Medical therapy includes using systemic anti-inflammatories such as phenylbutazone, meloxicam and firocoxib to reduce inflammation and pain.

“Treatment for kissing

spines is varied…”

Targeted injections into the spaces between and around the affected spinous processes can also be used. The more common of these being cortisone or other anti-inflammatory medications into the space between the dorsal spinous processes to reduce the pain and inflammation. In some cases, shockwave therapy has offered good relief, and this can be done fortnightly. Medication and shockwave therapies usually incur withhold times with most racing and competing authorities and this needs to be considered before any treatment is done close to competitions.

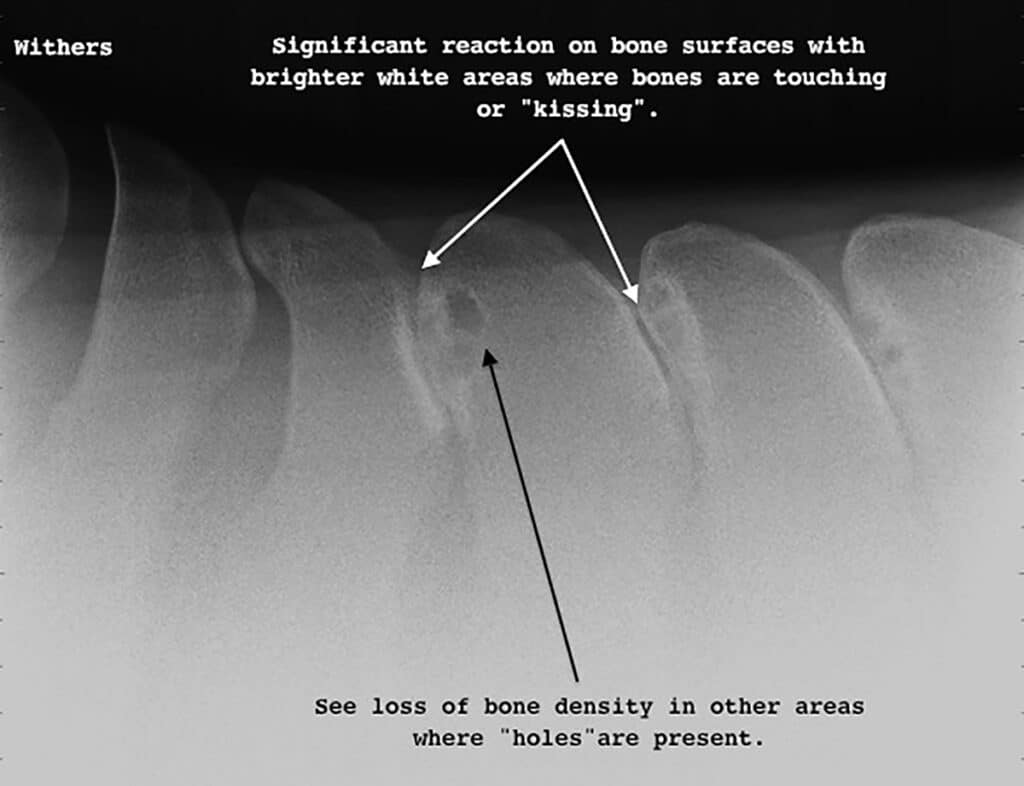

Severe kissing spines where there is significant reaction on the bone surfaces and also a loss of bone density.

Surgery procedures have had variable success, so techniques have been modified over years based on the success and failures these techniques have had. Depending on the degree of overlap and degeneration, surgery can vary from cutting the ligament that connects the dorsal processes, to shaving off an area of bone, to removal of a large piece of the affected spine or in some cases the spine itself. Generally, the more invasive the surgery, the longer time out is required for the horse to recover, and this follows true with kissing spine surgery.

Cutting the interspinous ligament, the ligament between two spines, offers relief by reducing the tension on the ligament which in turn decreases the pain. This can be done through a very small incision, and the healing time is several months. When large portions of bone are removed the surgical site is large and invasive, requiring extensive time out of work (usually over 12 months). Bone shaving is less invasive and therefore requires less time for healing.

Following surgery, rehabilitation is very important to ensure the back and support structures of the spine are strengthened before the workload on the back intensifies. The prognosis following surgery is fair to good, with some horses making a full recovery and returning to competition successfully, while others still retaining some pain and weakness. EQ