An understanding of how to develop the proper outline, collection, and the resulting elevation of the forehand is crucial to developing a correct dressage horse.

“The horse should be capable

of carrying you with ease…”

To begin with, you need a horse that is built specifically for your discipline of interest. It’s much the same as a person who is over six-foot tall being suited to basketball, compared to a person who is under five foot and more suited to weightlifting. It is the same for the sporting horse.

The first thought that comes to mind is that the horse should be capable of carrying you with ease. Is the horse well balanced (meaning, is his spine already near to the horizontal)? As we know, the spine is sloping downwards from the back to the front, ending at the last neck vertebrae (number seven), which is approximately the widest part of the base of the neck.

This location of the last neck vertebrae and the first thoracic vertebrae (the vertebrae in the back that the ribs are attached to) we like to be high in relation to the hips. Placing ourselves behind the horse, we would like to see the withers higher than the croup.

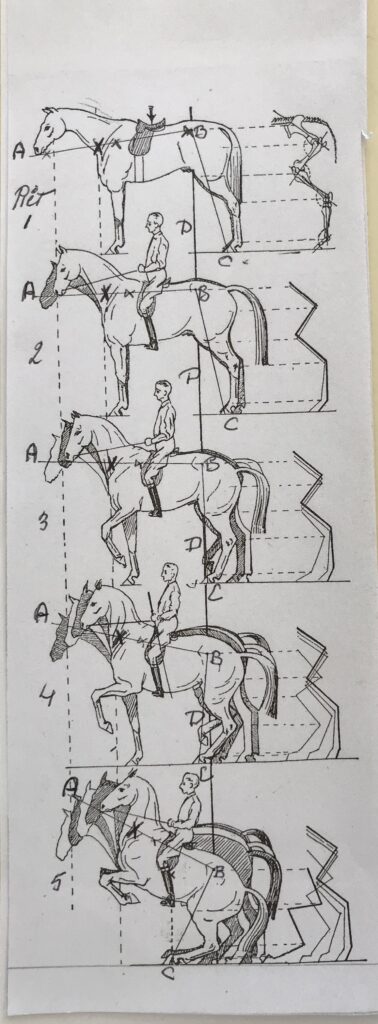

The illustrations (1-5) are self-explanatory, however, I would like to emphasise certain aspects. To be really accurate, it is not so much that the forehand rises, it is more that the hindquarters are lowering. A horse that is up in front without lowering behind is hollow backed.

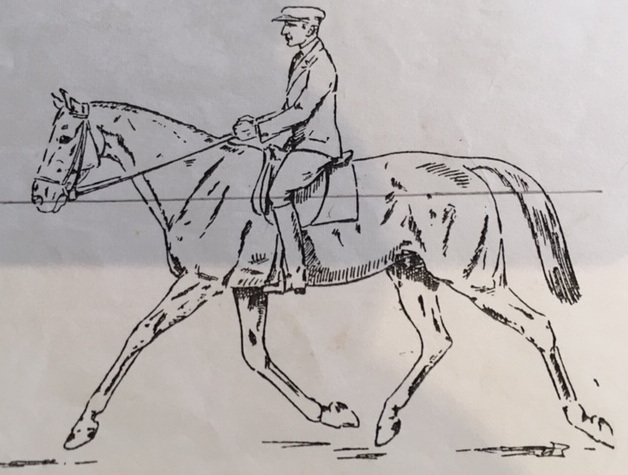

We would like the horse to move forward with calm, regular, long strides — not short, quick strides. Why? Because only with long strides will he flex his joints in the hind legs and lower his croup. In the landing phase, the joints are still slightly flexed so they can develop the spring quality, but more importantly, that’s the only moment for the application of the half-halt in the future.

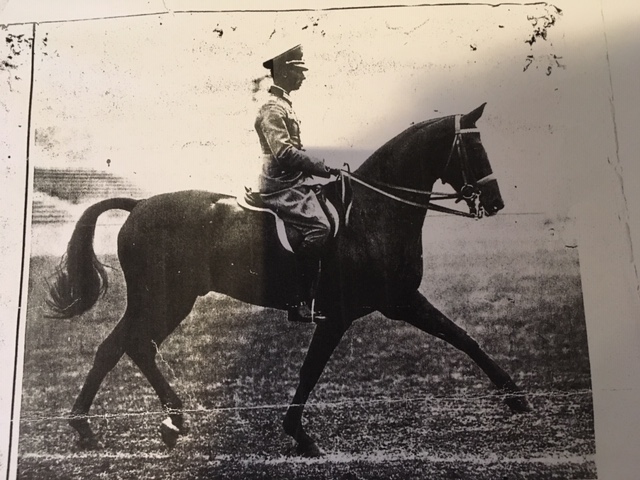

If the horse goes with short steps, he is avoiding the gymnastics and taking the easy way out (less tiring). Try it yourself by sinking and bending the knees as you move. As the horse is lowering the croup (hindquarters), his spine will become more horizontal and the horse will be less on the forehand. Automatically we get more rising of the forehand due to the lowering of the hindquarters, (relative rising of the forehand).

A prerequisite, of course, is the foundation: forward, loose, straight, and then last but not least, collection.

“A prerequisite, of course, is

the foundation: forward, loose,

straight, and then last but

not least, collection….”

FROM LONG & LOW TO LEVADE

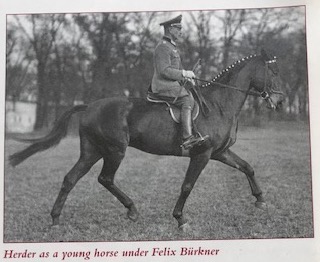

In diagram one, the hind legs are actually a little too long and out behind; I would love to see a straighter line down to the straight, standing cannon bone of the hind legs. In this picture, the outline of the horse is long and low. The young horse should not be any lower, unless his back or hindquarters are inclined to be weak, but certainly no more flexion at the poll.

A young horse working according to diagram 1.

Over-flexing the poll and bending the neck downwards with the face behind the vertical should be avoided.

The picture in front of the rider must correspond with the picture behind the rider and vice versa.

Horses who are weak in the back or in the hindquarters can be ridden as in diagram one, a little lower. The amount of flexion must be in relation to the rising of the neck. The lower the neck the less flexion, the higher the neck the more flexion.

I would like to emphasise again that flexing the poll and rounding the neck upwards go together, without showing a convex under neck. The horse that has a long, thin neck needs a rider with good hands to avoid the horse over-flexing downwards and perhaps finishing up with a false kink behind the third neck vertebrae. When this false kink happens, the connection is lost between the front and back — and the aids finish up nowhere.

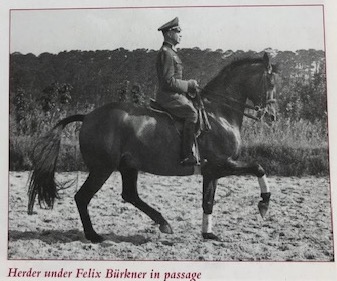

The same horse a little older, working as per diagram 4.

It is sad to see that many riders deliberately manipulate the face of the horse downwards so it can’t even see where it is going. My thought is that they think it’s correct or are frightened to lose control over the horse. We shouldn’t make “bridling” a horse a specific exercise; it should develop gradually as the horse becomes stronger and more collected, through half-halts.

One of the most common mistakes made by riders is the unhealthy desire to manipulate with their hands. By doing this, the rider merely acts upon the bars of the mouth and will never achieve permeability, but will end up with over-bending the neck.

The prerequisite for collection is a horse which engages the hind legs well under the rider, lowers the hindquarters and takes more weight onto his hind legs. The ultimate goal is piaffe (picture four) and in the case of classical dressage, levade (picture five). EQ