I want to continue our exploration of what we might learn from science, and look at chewing behaviour. Practitioners of natural horsemanship, and others, have taught us that the horse will lick and chew as a sign of submission and relaxation. Is there any truth to this?

Is licking and chewing a sign of submission or stress?

Experienced horsemen and women have observed wild horse herds and noticed that licking and chewing and lowering of the head were apparently communicating submission to other horses. This has been promoted widely in natural horsemanship circles. For example, Monty Roberts teaches that when working with a horse in the round yard, doing his Join-Up technique, the trainer moves the horse around watching for him to show signs of submission, such as licking and chewing, and putting his head down. When the trainer sees these signs, he releases the pressure by changing his posture and stopping pushing the horse, and the horse “joins up” and comes in to the trainer.

I have used this method and find it has some usefulness. Of course, there has been some criticism about chasing a domesticated horse away when actually they want to be with you anyway. Warwick Schiller came to Australia recently. He teaches that licking and chewing is a sign that the horse has moved from the adrenaline-charged Sympathetic Nervous System (so-called “Fight and Flight” reactions, associated with stress and arousal) and into the Parasympathetic Nervous System (“Rest and Digest” or “Feed and Breed” associated with relaxation).

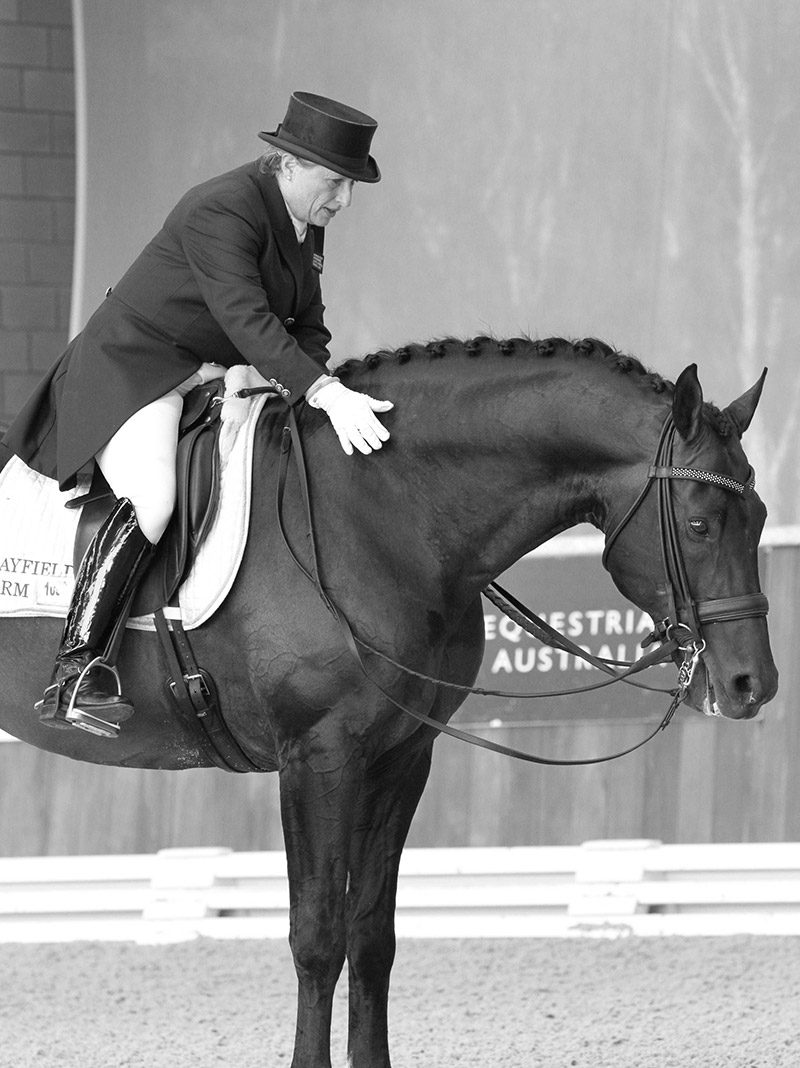

Mayfield Farm’s Horse of the Month

Mayfield Farm produces quality young sport horses, and currently has a number for sale that are under saddle and ready for you to enjoy. Stud principal Kerry Mack offers the featured horse of the month, Mayfield Zelda.

Zelda is an eye-catching five-year-old dressage mare, by imported dressage stallion Mayfield Pzazz out of a quality Rotspon mare.

Zelda has three quality paces with a particularly balanced canter. She is currently training the changes and Elementary work. As well as showing talent for dressage, she would also suit someone looking to do other disciplines, as she shows good technique over a jump, and has the conformation and eye catching looks to be competitive in the show ring. She also had a beautiful foal as a four-year-old.

View the Mayfield Farm website for more young horses for sale.

“A prey animal such as

the horse learns better

when relaxed.”

A prey animal such as the horse learns better when relaxed, so we want to be able to recognise signs of relaxation. For example, when working with the horse in hand, Warwick will watch for these signs. He encourages you just to be with your horse as a relaxed presence and wait until he shows licking and chewing. So, is this science or pseudoscience?

When I looked for scientific papers supporting that chewing behaviour was associated with the parasympathetic nervous system, I found nothing. In the book Evidence Based Horsemanship, Dr Steve Peters, neuropsychologist, writes that “a response to stress will release adrenaline and lead to a relatively dry mouth. The horse starts licking with the return of saliva secretion when the balance of the sympathetic and parasympathetic chemical reactions return to their set point.”

The International Society for Equitation Science (ISES) facilitates and promotes research into horse training that may “enhance horse welfare, and improve the horse and rider relationship”. At the ISES conference in Rome in 2018, trained scientists Margrete Lie and Professor Ruth Newbery presented their findings, having asked the questions: “Is non-nutritive chewing performed to signal submission to another horse?” and “Do horses chew in between stressed and calm situations?” Non-nutritive chewing that they examined is, of course, when a horse chews with his mouth but there is no food.

HORSES IN THE WILD

They observed wild horses living in natural herds, where about 200 horses were living in a 334 square kilometre park in Ecuador. They observed for 80 hours and collected data on 202 interactions where licking and chewing was observed. When they looked at aggressive interactions, such as when one horse was threatening another, they found that chewing was more often performed by the aggressive horse. There is no comment in the paper whether there was a difference in the type of chewing behaviour, e.g., were the incisors exposed with the lips drawn back?

They also looked at what was happening before and after the chewing and studied whether chewing (non-nutritive) occurred between tense and relaxed situations. They found that “the majority of behaviours before chewing were tense, and the majority of behaviours after chewing were relaxed. The chewing behaviour occurred when the horses transitioned from a tense to a relaxed state”. The researchers wondered if rather than chewing representing a communication between the horses, it may be that a horse has been in a tense situation, (with the sympathetic nervous system switched on), and consequently will have a dry mouth. When the tense situation resolves, the horse licks and chews in order to lubricate his dry mouth. I think that this is the observation that has led to the interpretation that the horse has moved from sympathetic to parasympathetic tone.

All horses showed the chewing, not just the submissive horses. The researchers cannot tell from these observations whether the chewing comes because the horse is relaxed, or if the horse chews in order to relax. Further research to tease this out would need to measure stress objectively (for example, the heart rate variability we visited last month).

OVER-TIGHT NOSEBANDS

This research is especially interesting to me in the face of the current predilection of dressage judges to penalise horses who chew the bit. This has led to the awful practice of over-tight nosebands as riders, incentivised to maximise their marks, clamp the mouth shut so tightly that the horse sometimes has difficulty swallowing his saliva, resulting in the foamy mouth the judges prefer! Top judges such as Steven Clarke do not support this approach but it continues nonetheless.

Researchers have wondered if rather than chewing representing a communication between the horses, it may be that a horse has been in a tense situation and then begun to relax.

“All horses showed

the chewing, not just the

submissive horses.”

So, what do we know that signifies submission? ISES has an interesting and worthwhile position statement on the use and misuse of leadership and dominance in horse training, written in 2017. They make the point that the “predominant submissive behaviour is avoidance”. Well, this is interesting but doesn’t really help us as riders. Many of us have been taught that a horse as prey animal will lower its head in submission if it is relaxed, and will relax if he is caused to lower his head. The theory being that he will graze with his head down when he is relaxed, and will raise his head if he is tense or if he thinks that there may be a predator around.

Back in 2005, this common wisdom was examined in 20 horses in Paul McGreevy’s lab. They found that in fact lowering the horse’s head did not result in relaxation when scientifically measured. However, as a horseman, I know from experience that when my stallions or youngsters are fractious, if I lower their heads they become more cooperative. It may be that the ethological story about grazing and relaxation I have been telling myself is just wrong and the actual explanation may be more about overshadowing. I teach my horses to stretch their heads down so when I can get them to do something they know, some conflicts are resolved for them, the same way we use overshadowing for specific situations, such as clipping.

Kerry Mack has taught many of her horses to lower their head when relaxation is needed – including stallion Mayfield Pzazz. © Michelle Terlato

INHERENT BIAS

Bias is inherent in human observations. Science has studied this. The Nobel Prize has been awarded to scientists who studied bias. We know that humans are likely to notice what they expect to see. For example, most of us have seen a foal lower his head and open his mouth and chew when he’s approaching an older horse. If we see this as submission we are more likely to then notice other interactions when chewing is a part of submissive behaviour. We may also just not notice when we see chewing as part of an aggressive behaviour. So, an untrained person is more likely to notice things that support their ideas than a trained scientist, who will put things in place to minimise bias, for example, having video rated by more than one trained observer.

Of course, some really important discoveries have been made by lay people. For example, Faraday was a bookbinder who discovered electricity and magnetism. Much of what we do in equestrian pursuits has been the traditional wisdom of what works. Sometimes the stories we tell ourselves about why something works are not accurate, even if we know it works. Science is all about asking questions to get a deeper understanding. Don’t be afraid to ask questions. Ask a question of yourself and search online to see if someone has studied this and has found an answer. If a trainer uses science to argue his case, don’t be afraid to ask about the source. Beware of pseudoscience where practices are claimed to be scientific but may not be. Of course, just because a question doesn’t have a scientific answer doesn’t mean the colloquial knowledge is wrong. EQ