Wintertime brings with it the dreaded foot abscess. Whilst most cases will cause a temporary acute lameness, some go on to cause weeks or even months of stress to both owner and patient, and occasionally result in the need for surgery.

An old horse with Cushings that has a foot abscess.

The horse stands with front foot pointed in front of the body (toe pointing).

Wet and muddy conditions soften the foot and allow bacteria to gain access through the white line, which is the junction between the sole and the hoof wall. It is a natural line that delineates the hard, non-sensitive part of the foot, or the hoof wall, and the sensitive structures of the foot, or the laminae.

Cracks in the hoof wall or minor traumas to the sole of the foot add to the increased risk of the horse developing an abscess in these conditions. Once the bacteria enter the hoof, they multiply and cause the production of pus, which builds up into a pocket, causing pressure and pain until an exit point is found and the pus can escape. Ideally, this involves the farrier or veterinarian locating the site of the abscess and using a hoof knife or similar piece of equipment to open the abscess, allowing pus to drain down through the sole. Often in cases where the horse does not receive any farrier or veterinary care, the pus will find the easiest path for drainage, the one with the least resistance, up through the coronary band. This is not ideal as the pus needs to track upwards to be discharged, and once the pressure has been released, it can be difficult for the pus at the lowest point inside the hoof to drain.

HOW DO I KNOW MY HORSE HAS A FOOT ABSCESS?

Most horses with a hoof abscess will show a lameness that progressively gets worse over several days until the horse becomes severely lame, sometimes even non-weight-bearing lame. Clues that indicate the foot may be involved include: the horse standing with a front foot stretched forward of the body (front foot abscess) or the horse taking weight on the toe of the affected foot while standing or trying to walk. With hind feet, the horse can hover the affected foot just above the ground before it places the foot down.

On closer inspection, the foot is warm or hot to touch, and for those able to palpate a pulse, a bounding pulse can be felt. As the lameness progresses and the infection builds, there is often swelling of the lower limb, predominantly from the coronet up through the pastern to the fetlock. In some cases, the swelling can move up into the cannon area towards the knee as the infection moves from the abscess and into the soft tissues of the limb. Hoof testers can be used to help localise the site of the abscess as the horse is usually sorest where the pocket of the infection is located. This can take a bit of finesse to detect as certain horses can show response all around the foot and careful, fine application to different areas may be required for the sorest area to be defined. On some occasions, multiple abscesses in more than one foot can occur and this can make diagnosis challenging, as the horse appears to have difficulty in walking or will not walk, and other causes must be ruled out.

WHAT DO I DO IF I THINK MY HORSE HAS AN ABSCESS?

The obvious answer is to seek professional advice, either from a farrier or a veterinarian. Unfortunately, this is not always possible. Until the abscess has been opened, or burst, the horse will usually remain lame. If veterinary or farrier attention cannot be sourced initially, then the foot should be soaked in warm, salty water to encourage the abscess to come to a head. This makes it easier to open if a qualified person can attend the horse or allows it to burst through the coronary band and promote drainage through this opening. If the abscess does burst of its own accord, then the hoof should continue to be soaked for several days to ensure that all the infection has completely drained.

The use of commercially available poultices has taken over from the practice of soaking the foot, however, in some cases, soaking the foot can provide better results, particularly in the more stubborn cases where the abscess cannot be opened or can take an extended period to burst on its own. I would typically soak the affected foot twice a day in salty water (often using Epsom salts), as hot as the horse will tolerate, which usually means as hot as the human hand can stand. Povo-iodine can be added to the water to act as an antiseptic, but I have not always found this necessary. Once the foot has been removed from the water and dried, apply a poultice to the hoof, so the area is kept clean and the abscess encouraged to drain/burst.

I am often asked if the poultice should be put on wet or dry. In the initial stages the poultice should be moistened with warm to hot water, as a poultice needs the moisture to draw. The disadvantage of continuing to use a wet poultice is it can make the sole waterlogged and predispose it to other conditions. Similarly, continuously applying a wet poultice to the coronary band can cause damage to this structure, so a balance needs to be found. Applying a wet poultice for a couple of days, then a dry one to allow the coronary band to dry, often works well. Once the abscess is open and pus is draining from the area, a dry poultice can be used, as the pus will wet the poultice and encourage more drawing of pus onto itself. As the abscess resolves, there will be less discharge onto the poultice, which has a self-limiting effect on its drawing ability. If in any doubt as to how the abscess is resolving, seek the advice of a veterinarian or a farrier.

This is a foot abscess that wouldn’t heal; see subsequent X-rays below.

“Hoof infections are one of the

biggest causes of tetanus.”

DOES MY HORSE NEED ANTIBIOTICS OR OTHER MEDICATION?

The use of antibiotics for a foot abscess is controversial. In most cases, if good drainage can be attained, then the use of antibiotics is not required. In some cases, yes, antibiotics will be required but this is usually in cases where the infection has spread up the limb into the soft tissue structures. If the deeper structures of the foot become involved, such as into the pedal bone, where soaking and/or poulticing is not as effective, then using antibiotics may be necessary. Using antibiotics too early in the developing stages of any abscess can result in dampening down of the abscess, so the horse improves in its lameness and clinical signs but does not resolve the problem. Once the horse stops the antibiotics, the abscess can flair back again, but often in these situations, the abscess does not proceed to the point of bursting but can linger for weeks and weeks, leaving the horse lame and the owner frustrated (as well as the vet!).

THE USE OF TETANUS PROPHYLAXIS IS ESSENTIAL

Hoof infections are one of the biggest causes of tetanus and it is crucial that any horses with hoof abscess are covered for tetanus, either by way of having had their full course of tetanus vaccinations, or by the administration of a tetanus antitoxin at the time of the injury. The antitoxin only gives coverage for about a month so previously unvaccinated horses that require treatment with the tetanus antitoxin, should then be given a proper course of tetanus vaccinations.

Pain relief such as phenylbutazone (“bute”) may be administered in some cases, although it rarely makes the horse look a lot better in the period when the abscess is developing. It can potentially help with the intensity of the pain, but most horses will still be quite lame when they walk. There is a theory that horses on “bute” may walk more and so put more pressure on the abscess to burst out, but this has not been proven. It does make the owner feel better giving the horse some pain relief, and in most cases causes no harm if given at the correct dosage for a short period of time.

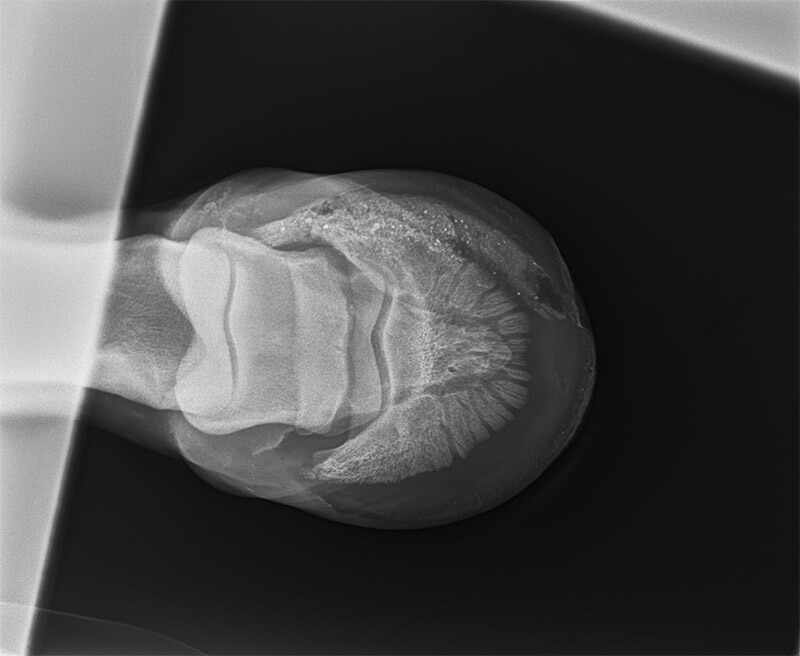

A – An underrun sole; this is the X-ray showing debris inside the hoof. B – This is an X-ray after the muck was syringed out of the hoof. The large black hole is the clean cavity.

“The underrun sole occurs when

insufficient drainage occurs and the abscess

spreads along under the sole.”

The sole was opened to clean out the muck and the horse was much improved after.

WHAT COMPLICATIONS CAN OCCUR?

The most common complications that can occur and change a simple foot abscess into an ongoing saga include: an underrun sole, infection of the soft tissues in the hoof and an infection into the pedal bone. The underrun sole occurs when insufficient drainage occurs and the abscess spreads along under the sole, sometimes bursting out in multiple places around the foot and causing ongoing lameness despite the abscess having been opened. Sometimes pus can still be seen to be draining and other times not, but the horse continues to look like it has an abscess for weeks after the initial diagnosis and drainage has occurred.

In these cases, a large cavity exists between the old sole and what has become the newly keratinised sole (so the pedal bone is not exposed). Pus and sometimes debris are caught between what are effectively two soles, causing an ongoing lameness. The farrier will sometimes pick this up when examining the foot, knowing that multiple break outs have occurred, and the abscess has been “going” for several weeks. On other occasions the vet may diagnose an underrun sole after X-rays are taken due to the chronic nature of the lameness. Once the dead sole is pared back and the pus or debris removed, the lameness usually resolves quickly and the horse can return to work, although it may require some packing of the foot with iodine swabs or some form of sole packing, until the new sole is fully formed and hard enough to resume normal wear.

If the infection spreads into the soft tissue structures of the foot or the lower limb then, as mentioned above, antibiotic therapy may be required. This may take the form of systemic antibiotics injected daily or given as an oral paste, however, if the infection spreads into the area around the navicular bone or into the coffin joint, this can require more intensive antibiotic treatment. In these cases, if an infection is diagnosed as involving the joint or navicular bursa, antibiotics may need to be placed directly into these structures following the infected areas being surgically flushed or the horse may require a procedure called Regional Limb Perfusion (RLP). This is where a tourniquet is placed above the fetlock and a suitable antibiotic is injected into a vein below the tourniquet, resulting in a high level of antibiotic flooding the affected region for an extended period (20-30 mins). This procedure may need to be repeated daily or every couple of days.

On some occasions the infection can involve the pedal bone, and if this does not resolve with systemic antibiotics or RLP then surgery to open the sole and debride the infected pedal bone is necessary. This can be done on the sedated standing horse or may require general anaesthesia if the horse is uncooperative or the pedal bone infection is particularly large. Once the pedal bone has been opened and debrided then the wound will need to be treated daily and a hospital plate applied to the shoe until the underlying area is filled and keratinised enough to protect the foot.

While most foot abscesses are more of a nuisance than a major cause for concern, it pays to treat them carefully and be mindful of the possible complications. So, this winter, be aware and wary of this common ailment! EQ