Every horse is special, but some actually become legends. Sefton is one of those, a hero of the IRA bombing at London’s Hyde Park in 1982. Seriously wounded, he fought back to health and entered the annals of history as the horse who refused to die.

The legend of Sefton started in Ireland – Waterford to be exact, traditionally celebrated for its fine and precious crystal. Well, Sefton was not particularly fine and certainly not very precious when he was a youngster, the result of a liaison between an Irish Draught mare and a local stallion. He was not even given a name in those early years, but his anonymity did not last for very long – as the story goes.

Call it blarney or a true account, but the Sefton story really began when he was a yearling and taken to a horse sale where he was one of a crowd but still managed to catch the eye of Michael Connors, well-known horse trainer who owned Tullyvolahane Farm and a recognised supplier of horses to the British Army.

The young horse spent much of his time with other youngsters in the sprawling paddocks of the farm, but one day – and this is where we need to decide between fact or blarney – the local Woodstown Harriers hunt passed nearby in full pursuit of a quarry. The young horse pricked up his ears and then his hooves, jumped out of the paddock and joined in the hunt including leaping over some of the highest walls in the land. Michael Conners brought him back but realised that this was no ordinary horse; little did he know just how special this four-white-sock animal was going to become.

Sefton was part of the cavalry for the British Royal Horse Guards. Image supplied.

“He was still holding

Sefton whose jugular

had clearly been severed.”

As Commander of the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment, Brigadier Andrew Parker-Bowles later became well acquainted with Sefton and played a major part in saving his life. “I think Sefton could be described as a character and could never be considered a novice ride, although those who did ride him – myself included – always considered it to be a privilege,” he says. “In fact, he became something of a humorous prize as the best rider of the week in training was given the opportunity to ride him. I took him round the park a number of times myself and he was always alert and ready for action. I think if he saw a piece of litter blowing across the grass he would have chased it had he been given leave to do so.”

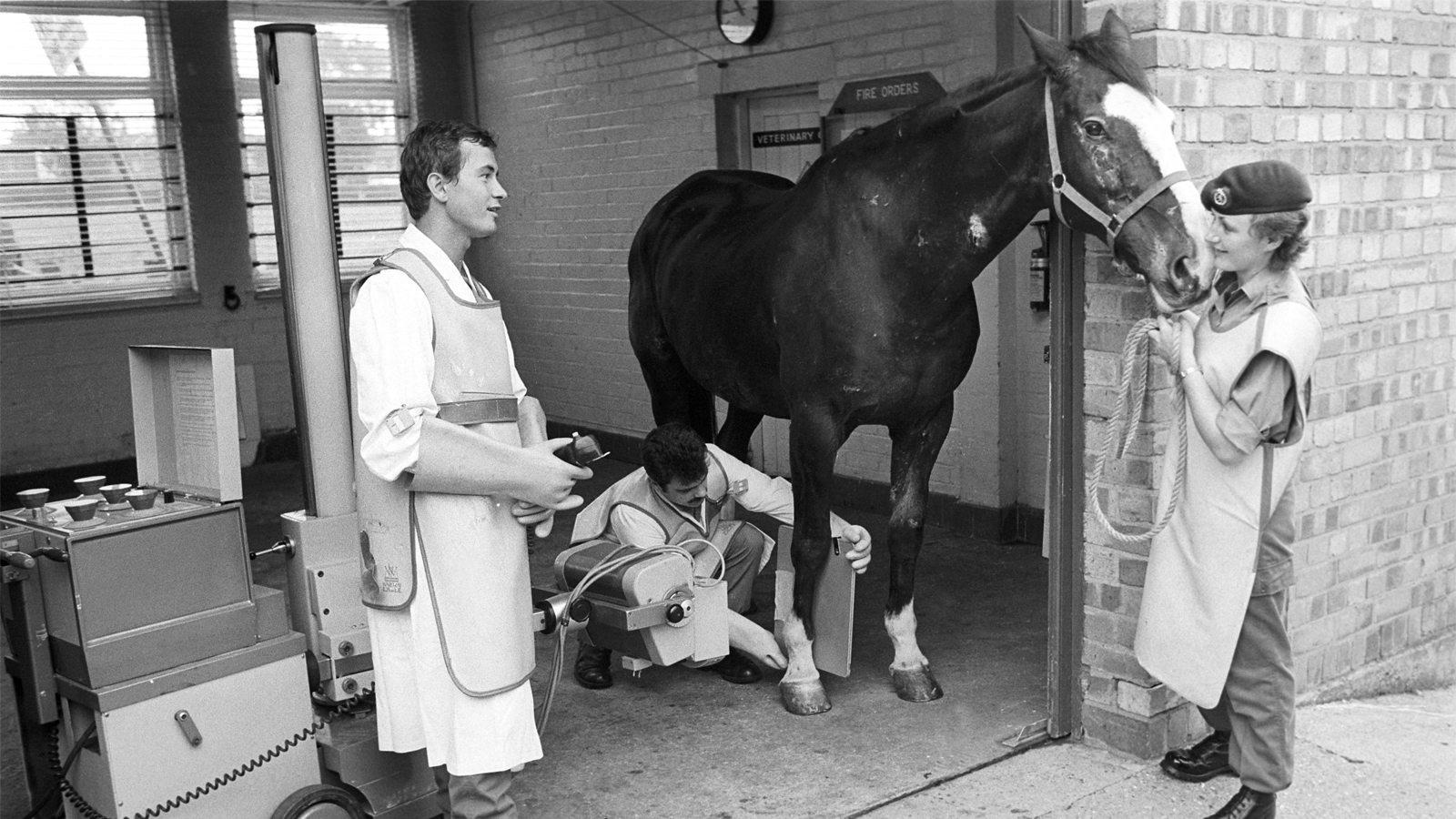

Arriving in England from Ireland the young horse found himself engaging daily in experiences that were very new to him. He travelled on a train to Melton Mowbray where the Army Veterinary Corps Centre welcomed him into a fine loose box, introduced him to inoculations and shoes and the joys of worm powders. Clearly Sefton was “in the army now, my lad”.

ANSWERS TO ‘5816’

At this point he was still not actually called Sefton but answered to ‘5816’ and that was how he was then introduced to Trooper Douglas McGregor who was himself recently on a training course at Melton just as 5816 had been. The two were to get to know each other well, beginning with simply walking and getting to trust each other. When the real work began, 5816 reminded McGregor that while he was willing to cooperate – up to a point – he was still his own horse and had the right to the odd tail swish, buck or even a leap forward now and then.

Would he ever make a ceremonial horse? There were doubters but Major HO Hugh-Smith of the Royal Horse Guards was not one of them. He saw something in 5816 and was delighted to be able to take him on for the Royal Horses Guards (nicknamed the Blues) after the toss of a coin. In a short time 5816 was given his regimental number of RHG 61, but he still lacked an actual name. That year all the new horses were to be given names beginning with the letter “S”. Thus RHG 61 was named in honour of Major the Earl of Sefton… and so Sefton, who we were all to come to know and love, finally become more than just a number. No one was more pleased than Trooper Douglas McGregor who was to continue their partnership.

Sefton’s training intensified and McGregor discovered that his pal was a naturally gifted jumper. He also discovered that no matter what, Sefton still had a mind of his own and question marks arose again as it became clear that ceremony meant nothing to him. He hated the regalia, the special harnessing and the pomp and circumstance and even misbehaved at Trooping the Colour.

It was on 20 July, 1982 when the world was shocked by an IRA attack in London. It was around the time of Sefton’s 19th birthday and the day had started with the usual early morning routine of feeding, grooming and dressing before going on guard duty in Whitehall. One person was missing – Trooper Adrian Philips, Sefton’s regular rider. They were completely compatible and regularly named as best horse and rider, which was why they most often had one of the coveted roles of being stationed in front of the Whitehall sentry boxes and constantly photographed by admiring tourists. Sefton loved it. Trooper Philips was on leave on this day and his place in Sefton’s saddle was taken by another accomplished horseman – Trooper Michael Pedersen.

DAY OF HORROR

At 10.35am the Queen’s Life Guard of 16 men and 16 horses left the barracks for the familiar journey to Whitehall accompanied by an escort of two mounted policemen. Just before they reached Hyde Park Corner it happened – an explosion that suddenly destroyed the peace of that warm summer morning and plunged the day into a deep ravine of horror that would leave a scar on the hearts of decent humans forever.

Four men and seven horses were killed and many others seriously injured, including Sefton upon whom 38 wounds had been inflicted. Andrew Parker-Bowles was the among the first on the scene and took control of the situation. “I heard the explosion and the commotion that immediately followed,” he recalls. “I heard someone shout ‘the bastards have got the horses!’. We knew that we had been hit and all that that would mean, we had to get there to aid our fallen. I sprinted all the way to the scene and it was indeed devastating to see. You have no time to look, you just have to get on with it. I saw Trooper Pedersen looking dazed and bloodied; there was a nail through his glove, having pierced one of his fingers. He was still holding Sefton whose jugular had clearly been severed. He was pumping blood. A Life Guard, Corporal of Horse O’Flaherty, had arrived on the scene and he was covered in blood as he pushed his fist into Sefton’s main wound to try and stem the flow.

Sefton in recovery following the 1982 bombings. Image supplied.

50-50 CHANCE OF SURVIVAL

“I told him to get a shirt into it as packing and somehow he found a couple of shirts and used them. It was a race against time for Sefton but he gathered himself and was led away from the scene to a horsebox which had arrived from the barracks. Veterinary-Major Noel Carding was quickly there and patched him up as best he could, giving him just a 50-50 chance of survival. All the men and horses were taken into care, of course, and we then heard that there had been a second bomb which had killed seven bandsmen of the Band of the Royal Green Jackets who were playing at Regents Park.

“Noel Carding worked for 90 minutes solid on Sefton when we got back to barracks and probably saved his life. There would be a lot more surgery and convalescence to come but Sefton himself was a fighter, a non-conformist who refused to give in.”

Sefton survived, of course. He carried fragments of that IPS bomb for the rest of his life, but he survived and became an icon, a symbol of defiance, a horse that refused to be killed. Sefton’s story and the veterinary support he received caught the imagination of the world. “We had to set a room aside for all his fan mail and gifts,” says Andrew. “There were donations of more than £620,000, which went towards the creation of a new surgical wing at the Royal Veterinary College which became known as the Sefton Surgical Wing.”

Sefton at Horse of the Year Show in 1982, where crowds flocked to honour the cavalry horse’s bravery in service

When, in October 1982, The Horse of the Year Show honoured Sefton, the packed audience rose to their feet to salute him, and few could hold back the tears as he proudly walked the length of the arena.

“Right to the end

he was still Sefton.”

Sefton in retirement with pal Echo. Image supplied.

Finally, Sefton made one last trip to Melton Mowbray in 1993. “I was with him,” Andrew explains. “He was now almost 30 and lame, his wounds had finally caught up with him and it was with regret that the decision was taken for him to go to sleep. He was in a paddock the evening before and, amazingly, he twice jumped the fence to sample some grass on the other side. Right to the end he was still Sefton.” Sefton was buried at Melton Mowbray and there is a statue of him at the Royal Veterinary College in Hatfield, Hertfordshire. EQ

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE TO READ:

The Horses in Peaky Blinders – Equestrian Life, March 2024