This article first appeared in a previous issue of Equestrian Life magazine. To read the current digital issue, click here.

The stretchy trot in the Preliminary tests allows the horse to stretch the neck forward and downward.

© Roger Fitzhardinge

By Uwe Spenlen

Why do young horses need to be ridden with the neck stretched forwards and downwards?

The method to stretch the horse’s neck forward and downward is postulated by the German Training Scale, also known as the International Scale of Education or Classical Training Method. It is not an arbitrary invention but based on a simple rule of nature. It has to do with the way the horse is built, how the horse is constructed, especially with his back and neck. The phrase ‘Classical Scale of Education’ doesn’t refer to an old fashioned, medieval training method but rather to a well tried and proven approach which emphasises good horsemanship. It’s just another word for natural dressage training. Classical equitation and education has existed for centuries and in my opinion it is the origin of all equestrian knowledge and this, and only this, is the basis of excellence in all disciplines. Classical rather stands for: Timeless valid and effective in form and subject matters, matured to meet all requirements and high demands of modern equestrian sports education.

THE TRAINING SCALE

To ignore the Classical Training Method is to ignore the wisdom, experience and understanding of many generations of successful riders, trainers and veterinary professionals. My contribution is to try to give riders a different understanding of dressage. Therefore first of all, we – the riders, trainers, coaches and instructors need to clarify and understand how our partner, the horse, is built. Unfortunately just a few of the mentioned group of people have sufficient knowledge about this interesting subject, about their partner of equine nature. At the very least, responsible coaches should have more detailed knowledge about the functional anatomy of the horse.

To ignore the Classical Training Method is to ignore the wisdom, experience and understanding of many generations of successful riders, trainers and veterinary professionals.

Painting: Ludwig Koch (1866-1934)

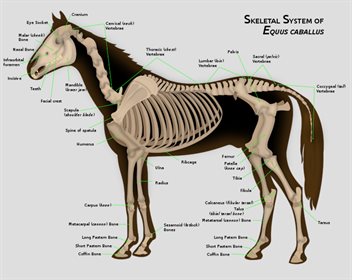

THE SKELETON

The skeleton of a horse, viewed from a lateral angle, presents a bridge-like structure, similar to a suspension bridge. The fore and hind limbs each act as a double pillar and the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae form the actual bridge-like connection between them.

The first part of the bridge consists of the thoracic (chest) vertebrae and of the lumbar (loins) vertebrae. These vertebrae are strapped together by numerous little joints as well as strong ligaments and muscles, which make this part of the spine extremely stable but give it only a little flexibility.

Attached to the lumbar vertebrae is the sacrum, which is formed by fusion of the sacral vertebrae and the tail vertebrae. The sacrum is connected with the pelvis through its broad wings and strong ligament.

It is here, through this joint, that the vertebral bridge receives the entire thrust from the hindquarters and transfers it along the back, transforming it into forward movement, through the poll to the horse’s mouth, and into the rider’s hand.

The skeleton of a horse.

THE VERTEBRAE

Please, let’s start again, going step by step from the front to the back end.

THE CERVICAL SPINE

In contrast to the thoracic vertebrae, the cervical (neck) vertebrae are highly flexible and comparable to the human spine. The cervical spine consists of seven large vertebral bones It forms a light s-shape, running downwards from the poll and goes into the thoracic spine between the shoulder blades, slightly above the point of the shoulder.

THE NECK VERTEBRAE

The head is attached in the poll to the cervical spine. The bone, which covers this joint, forms the starting point of the nuchal ligament. This point is extremely important for every trainer as well as riders to be aware of the precise location of the poll to the proper connection between the head and the cervical spine.

The area above the vertebrae is filled by a large ligament, the already mentioned nuchal ligament, which provides attachment for the muscles of the neck. There is a combination of large and small muscles in the neck. The longer muscle runs from the poll all the way to the forearm and from the wither up to the poll. The shorter muscles run from one vertebra to another or over a couple of vertebrae.

When the horse stretches his neck forward, the nuchal ligament is put in traction, pulling on the withers spinous processes, causing them to rise. This effect extends all along the horse’s back, the traction is transmitted to another ligament further back, which, as a direct continuation of the nuchal ligament, connects all of the back’s spinous processes. As the back’s spinous processes rise, upwards and forwards, the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae follows. As the result the horse’s back rises.

The muscles in the lower part of the neck, which bends the head down, should not play an active role. It is true that the horse should let the head and extended neck ‘drop’, not actively bend and not go on the forehand or even roll under. It should stretch forwards and downwards, seeking the rein and the bit from a yielding hand and not remain in a bent position.

BIOMECHANICS

The movements that occur at the neck are largely dictated by the shape of the bones. The joint at the poll between the skull and the first vertebrae ‘nods’, i.e.: that it flexes up and down only. The joint between first and second vertebrae rotates or pivots around a central axis. The joints from second to seventh vertebrae bend sideways with some combined rotation. The arching and hollowing, the up and down movements of the neck occur mostly between the seventh, the last cervical vertebrae and the first thoracic vertebrae at the base of the neck. The larger or longer muscles act to provide the gross up and down and side to side movements. The shorter muscles provide the more subtle and localised movements.

THE THORACIC SPINE

The connecting thoracic spine consists of 18 thoracic vertebrae which are considerably shorter and are inter-connected in a less flexible way, which means in a more limited range of motion. The 18 ribs are connected laterally via joints to this section of the spine. The first 8 ribs are known as ‘true’ ribs, the remaining 10 ribs are not joined to the breastbone anymore and are the so-called ‘false’ ribs.

THE LUMBAR SPINE

The lumbar spine follows on directly from the thoracic spine and consists of an average of 6 vertebral bodies.

THE SACRUM

At the end of the lumbar spine is the sacrum, a triangular bone consisting of 5 segments that are fused together. This bone is connected to the pelvis girdle.

THE BAUDAL SPINE

The tail spine is attached to the sacrum and forms the bony base of the tail and consists of 18 to 21 segments.

Just to mention it, an average-sized horse carries an estimated weight of 220–260 kg between its two pairs of limbs, (expecting mares even more). The natural effect of gravity means this weight is subjected to a vertical pull downwards and hangs on the bridge construction represented by the thoracic and lumbar spines.

An average-sized horse carries an estimated weight of 220–260 kg between its two pairs of limbs.

All the vertebrae of the back have prominent dorsal spinous processes of different length and angle. The first of the front vertebrae are angled towards the back, whilst those of the rear half point forwards.

The angle gradually decreases towards the middle vertebrae, of which the dorsal spinous process is upright. This indicates that certain spinal areas have different roles to play: The sacrum acts specifically as a support for the rear section of the vertical bridge whilst the neck and head can be perceived as a support for the front section.

THE UPPER TENSION SYSTEM

The upper tension system or upper brace is a band-like structure which is of considerable significance for riders as well as instructors due to its important function in carrying the abdominal and thorax weight.

A particularly important element of the upper tension system is the nuchal ligament. The tops of all the dorsal spinous processes are connected to each other by a strong ligament from which the nuchal ligament extends up to the head.

There is a second supporting mechanism in the form of the so-called lower lengthwise brace, running from the front (forehand) to the rear pillars (hindquarters) of the bridge. As described, the functional interplay of the skeleton construction and the muscles, the nuchal ligament and the back band, the upper tension, all play an important role in carrying the abdomen and the thorax.

An interesting question remains: How does the young horse cope with the rider’s weight?

When a rider mounts a young horse for the first time, the horse usually arches its back and contracts it in a spasm: it bucks. After calming down, it relaxes its back, e.g. it drops its back. If the horse is led, its walk is unsteady, sometimes swaying from side to side under the rider’s weight. At this stage the horse in effect carries the weight solely with its skeleton, without any support from its muscles. It is clearly obvious that the lower brace plays an important role because the horse, as it becomes progressively more tired, places its forelegs further forward and its hind legs further back, i.e. it simply ‘falls apart’.

THE LONG BACK MUSCLE

The central and very strong muscle which is particularly most important for the training of a young horse is the long back muscle, one of the most powerful muscles of the entire body. After a certain time the young horse can’t keep up the tension in his back, with the result that his back sags. As already mentioned, when this happens, the horse carries the rider’s weight more or less only with his skeleton, without muscular support. That gives the rider the impression that the horse ‘drops or hollows his back’. These expressions, however, are incorrect since they suggest that the dropping of the back is the horse’s fault, that he does it on purpose. He does not. He just reacts. He simply is exhausted.

Exactly here comes the point, where stupid riders reach for the draw-reins or even sharper bits.

It is therefore only logical that a supple young horse in extended posture wants to raise itself after a 15 to 20 minutes work and thus evade the muscle pain in the upper neck muscles. The well proofed fundamental Principles of Training do justice to this and prescribe dismounting in such a case and taking a break.

Horsemanship and the Training Scale inform us that each work phase must be followed by an appropriate relaxation phase.

Each work phase must be followed by an appropriate relaxation phase.

The rear base of this very powerful muscle is located in the area of the sacrum. Therefore it has a functional connection with the pelvis and sacrum. It is composed of many muscle layers. Its fibres run forwards-downwards to the transverse processes of the lumbar spine area. It runs along the entire lumbar and thoracic spine from the rear to the front and ends at the seventh cervical vertebrae.

The long back muscle is connected by broad back and buttock muscles to the fore and the hind limbs and thus function in the same rhythm of the movement. A free, elevated and rhythmic gait is only possible if the long back muscle swings naturally and elastically without being restricted by the rider and his weight. If the muscle is activated at its rear point of origin, it raises the forehand whilst the back is arched. If the muscle contracts from its front point of insertion it bends the back downwards.

Just another reminder: The correctly worked young horse needs 18 to 24 months of unspectacular gymnastic schooling before its body is so well trained to go further. We must focus our attention on the supple swinging back as the focal point and most important requirement.

READ THE LATEST NEWS ARTICLES HERE