Sesamoid bones, although only small, are associated with many important ligaments and tendons and play a vital role in the musculoskeletal system. Tiny fractures can occur during intense exercise and jeopardise the future of equine athletes if not allowed to heal thoroughly.

Sesamoid bones are located at sites close to a joint, where a tendon must change the direction of its pull, for instance at the back of the fetlock or the front of the stifle (the patellar is a sesamoid bone). These bones operate like a pulley wheel in a production line and allow the tendon to glide smoothly as it changes direction while the horse can maintain an efficient and fluent action, at the same time minimising the damage that can occur to the tendon whilst under the strain of full extension.

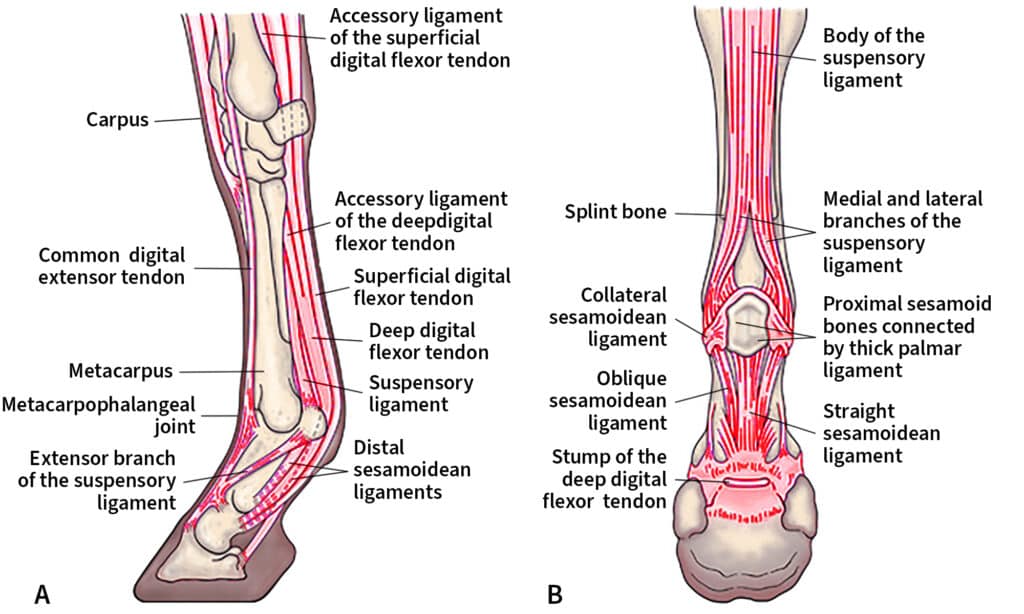

The horse has three sesamoid bones in the lower limb, and in this article we will focus on the two proximal or upper sesamoids located at the back of the fetlock joint. The third sesamoid bone in the lower limb is the distal sesamoid, aka the navicular bone. The deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) goes from running straight down the back of the leg to a forward incline at the back of the fetlock and along the pastern. Finally, it changes direction again as it attaches to the bottom of the pedal bone and is an example of how all three sesamoid bones are involved with the functioning of one tendon.

INJURIES READILY DIAGNOSED

Many injuries involving the sesamoid bone are readily diagnosed clinically but there are instances where more advanced imaging is required. Occasionally, scintigraphy is used when the site of lameness is unidentified, but usually nerve blocks would be effective at localising lameness to the sesamoid region. X-rays are the standard tool to identify most sesamoid fractures and injuries but there are some instances where CT, MRI or PET scans are required to identify subtle lesions or incomplete fractures.

Among the major injuries seen with the sesamoids are fractures. There are several predilection sites where these fractures occur and the prognosis for full recovery is determined by their location. The four common sites are apical (the top), midbody (horizontally through the middle), basilar (horizontally through the base) and abaxial (along the back of the sesamoid where the suspensory ligament attaches). There are other types of fractures that occur, but these are less common.

A lateral view of an abaxial fracture in the right hind fetlock. Image supplied by Dr Maxine Brain.

Sesamoid fractures are usually associated with high-intensity exercise in combination with fatigue, as the sesamoids and associated ligaments are being pushed to their physical extremes during intense exercise. The sesamoids are pushed hard up onto the back of the cannon during high-intensity exercise with hyperextension (over-extension) of the fetlock occurring when the limb is on the ground and the fetlock is weight-bearing. This puts strain on both the back of the lower cannon and within the PSB. Under ideal training regimes, the lower cannon and the PSB “adapt” to these stresses by laying down more bone to give them more strength to combat the added forces.

Unfortunately, not all horses can adapt appropriately; whether the horse has inadequate innate qualities, or the training is not suitable for that individual, the result is excess mineralisation of the bone that renders the bone unable to absorb and redistribute the forces. This is because the bone loses its sponginess and becomes hard and brittle, a process known as sclerosis. Sclerotic bone is prone to microfractures and in extreme cases full-blown fractures may be seen in PSB, cannon bones and the carpus (knee). The PSBs don’t always fracture, as in some cases it will be the suspensory ligament or sesamoidean ligaments that tear first, with ligament strains more common in the earlier stages of training.

Treating fractures depends on the type of fracture involved, as the relationship with the suspensory ligament above and sesamoidean ligaments below can result in opposing forces pulling the sesamoid fractures apart in different directions.

Small apical fractures can be removed and the prognosis for a successful return to full training and competition/racing is good provided there is minimal damage to the suspensory ligament.

Midbody fractures usually carry the worst prognosis for a successful return to work, as the two pieces of the sesamoid are pulled apart. Placing a screw through the two fragments and pulling them together is currently the treatment of choice, however, the placement of the screw is very difficult task due to the attachment of ligaments to the sesamoid. The surgeon needs to avoid damaging the ligaments as much as possible because there is no point in fixing the fracture if the ligaments are irrevocably damaged. Other surgeries trialled include placing wire around the fractured sesamoid and the use of bone grafts.

Basilar fractures can sometimes be removed if small and accessible, via an arthroscope that is introduced into the fetlock joint, otherwise they can be left to heal conservatively. Success is determined by the size of the fragment and the degree of ligament attachment to the fragment.

A basilar fracture of the left fore fetlock.

FOALS CAN BE SUSCEPTIBLE

Foals are very susceptible to hindlimb sesamoid fractures, especially in cases where they are allowed to chase after their mothers in large paddocks. Exhaustion and weak hindlimbs predispose these foals to fracturing through the sesamoid when the fetlocks become over-extended. This is especially true in those foals where the ligaments and tendons are lax due to prematurity or prolonged gestation. This tendon laxity is commonly seen in newborn foals and the risk of fracture justifies why these foals should be semi-confined until their limbs strengthen. Ironically, not all these fractures are detected early in life, and some may only be discovered during routine examinations when the horse is X-rayed as a yearling for the sales or when in early training where the sesamoid appears elongated compared to the “normal sesamoid”.

Occasionally a horse will fracture both PSBs during high-intensity exercise and this is catastrophic in all but a few cases. This is because the loss of this fetlock support system results in the fetlock dropping towards the ground when the horse weight bears, and this results in the blood supply to the lower limb being stretched and potentially ruptured. Without a blood supply, the foot is then compromised, and if the blood flow is not re-established the hoof can become detached, requiring euthanasia on humane grounds.

SESAMOIDITIS

Sesamoiditis is an inflammation of the sesamoid bone that is associated with young horses and frequently involves the attachment of the suspensory ligament. It is a term that is poorly defined and has been used to describe a spectrum of changes, including excess vascular channels visible on X-rays to clinical lameness and swelling over the area of the sesamoid

A horse with signs of sesamoiditis.

“The sesamoid and the

suspensory ligament branch

are both commonly involved in

an episode of sesamoiditis.”

A lot of studies have been performed to categorise the seriousness of sesamoiditis, particularly with the interpretation of yearling Thoroughbred racehorses at the major yearling sales. Changes in the number and size of vascular channels have traditionally been used as a guide to a horse having “sesamoiditis”, but this has not been a clear indicator with many veterinarians disagreeing on the significance of increased vascular channels in the PSB. Certainly, when there are large numbers of enlarged vascular channels (>2mm) and other sesamoid changes such as enthesophytes, the consensus is there is a potential problem, and caution should be taken with either purchase of an individual or the suitability to work.

For me, true sesamoiditis is associated with clinical changes in the sesamoid region, including swelling, pain and lameness, either subtle or obvious. Because of the close association between the sesamoid and the suspensory ligament branch, the two are commonly involved in an episode of sesamoiditis.

A lateral oblique view of a right fore fetlock showing sesamoiditis (the large vascular channels show as black holes).

Diagnosis should involve both an X-ray to assess the sesamoid and an ultrasound to assess the suspensory ligament, as it can be the tearing of the ligament attachment that causes the pain and lameness. The inflammation is normally associated with young horses over-exercising when the sesamoids are compromised either by the horse having poor conformation, a heavy body type, inappropriate nutrition, or rapid growth rates.

TIME OUT OF WORK

Treatment is time out of work, and this can vary from a couple of months to a year, depending on the age of the horse and the degree of inflammation. If the suspensory ligament is torn, the time out of work required is dictated by the degree of ligament damage. Shockwave therapy has been used to help facilitate the attachment of the ligament back onto the sesamoid, and whilst this may shorten the length of the healing process, it is no substitution for time.

Due to their proximity to the ground and the lack of fleshy protection over the surface of the sesamoid, traumatic injuries to the area are common. Whilst most can be resolved with basic first aid treatments, wounds involving damage to the bone and wounds that pierce the sesamoid can be serious if not treated appropriately and quickly. If a wound does cause infection of the bone (osteomyelitis), intensive antibiotic therapy including regional limb antibiotic profusions may be required. This is where a tourniquet is placed on the limb above the sesamoids and high concentrations of antibiotics are injected and then maintained within a small area to combat the infection.

This x-ray shows a defect remaining several months after an infected piece of sesamoid bone (sequestrum) was removed.

Osteomyelitis can also occur as a sequel to a septic fetlock joint or septic tendon sheath infection, making careful assessment and monitoring of the sesamoid bones a must when these structures are involved. Sometimes this requires more advanced technology than simple X-rays, as a significant degree of bone destruction is often required before a definitive diagnosis can be determined on plain X-rays. Regardless of the cause of osteomyelitis, if the infection cannot be treated effectively, euthanasia might be the only viable option for the welfare of the horse.

AXIAL SESAMOIDITIS

A rare condition noted for those readers involved with Friesian horses is axial sesamoiditis, sometimes referred to as osteitis of the proximal sesamoid bones. This involves a loss of bone on the top inside edge of the sesamoid bone that occurs in conjunction with damage to the intersesamoidean ligament (desmitis). It causes significant hindlimb lameness and the prognosis for future athletic performance in affected Friesians is poor. Friesians are not the only breed to have been diagnosed with this condition, however they are over-represented in the studies that have been performed, with no definitive cause yet identified.

“It is hoped that we can

all play a part in reducing

sesamoid damage.”

One of the theories is that the Friesian horse has an increased degree of fetlock hyperextension due to the laxity of their tendons and this causes damage to the blood supply and therefore damage to the bone and the intersesamoidean ligament. This theory is currently unproven and there needs to be a lot more research into this condition before any conclusions can be made regarding the cause. To the best of my knowledge, it hasn’t been reported in Friesians in Australia.

PSBs, despite their small size, play a big role in preserving the function and stability of the fetlock joints. By understanding some of the forces these small bones are subjected to and learning about the types of injuries that sesamoids can incur, it is hoped that we can all play a part in reducing sesamoid damage, or at the very least, be able to identify minor issues before they become major incidences. EQ