Horses can be great learners and can recognise your mood by your expression, but just how intelligent are they, and is it intelligence as we know it? How do we really evaluate how clever horses are?

How intelligent is your horse? Usually when we ask this question we ask from a very human-centric (anthropomorphic) way. When we say “my horse is smart”, we usually mean that we have seen something that makes us think that he thinks like us. We value language and logic and those things that from a brain anatomy point of view are functions of our so-called dominant (left) hemisphere, and our frontal lobes, the big part of our brain above our eyes that really distinguishes our brains from the brains of other mammals.

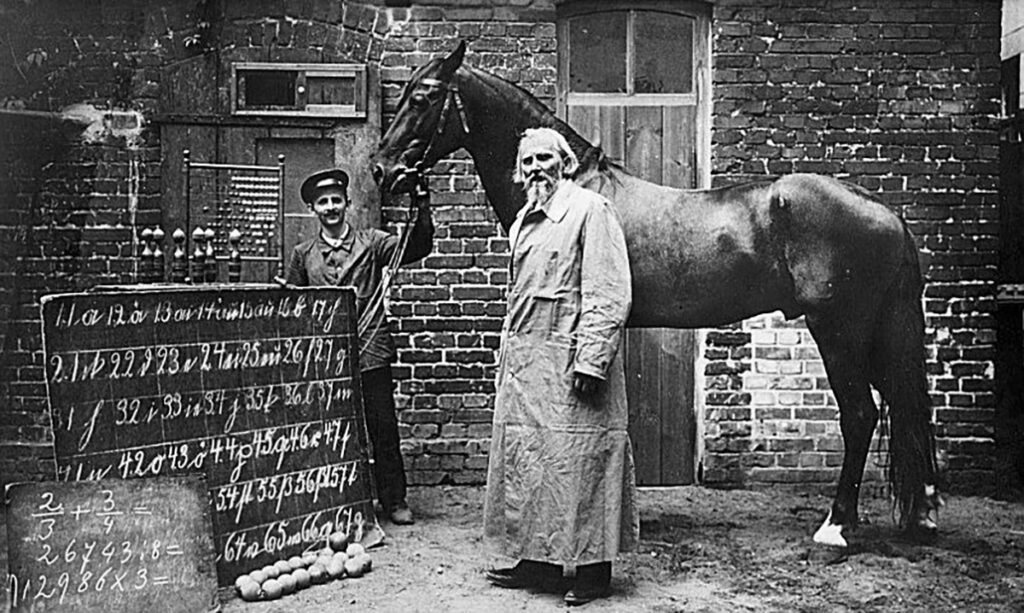

Clever Hans was a famous Orlov trotter in the early 1900s who had apparently learned to do arithmetic, including addition, subtraction, work with fractions, and even finding square roots. He was said to understand German language, spell, and be able to keep track of the calendar. His trainer really believed that he could do these tasks.

When Clever Hans was studied by scientists, they determined that Clever Hans was not clever at arithmetic. However, he was incredibly smart at responding to the non-verbal, unconscious cues of the person asking the question. He could tell that he was being asked a question by the person leaning forwards a little, so he would start to paw. Then he would tell when the correct answer had been given, and stop pawing when he saw the questioner react.

Clever Hans was a famous Orlov trotter in the early 1900s who could supposedly understand arithmetic.

Of course, it stands to reason that a horse would be very sensitive to postural cues. Firstly, we know that horses communicate with each other with non-verbal cues — a flick of an ear or tail, lowering of the neck etc. Secondly, think of those documentaries about African wildlife: the zebras and the wildebeests and the lions all lying around together in the sun. But if the lioness takes the posture of hunting, all the animals run away. Obviously, it is fundamental to a horse’s survival that they are sensitive to these cues.

So rather than ask “How smart is my horse?” a better question is, “In what way is my horse smart?” Let’s consider this, firstly, from the point of view of what we know about a horse’s brain, and then from some of the research done more recently. I am offering this not as a learned or exhaustive review of the literature, but rather a taste of things that I have found interesting.

We know from a range of studies comparing the anatomy of the brains of different species that it is fair to assume that anatomically similar parts of brains of different creatures perform similar functions. For example, the “smoke detector” part of our brains that alerts us to danger is called the amygdala, and in all the other animals with an amygdala it performs the same function. Actually, that includes most animals, mammals, birds, reptiles and even fish.

Horses in the wild need to be sensitive to postural cues from predators; it’s a matter of survival!

“Running away is their defence…”

There is another principle that the size of a part of the brain is proportional to the importance of the function of that part (the principle of proper mass is that the size of a part is in proportion to the amount of information that is being processed). Horses have very little in the way of frontal lobes, so we know that a horse is likely to have very little capacity for reasoning and logic, much less capacity for language, and very different memory functioning than us.

The principle of proper mass tells us that horses have large parts of their brains dedicated to movement. The cerebellum is a major centre for coordinating movement. Horses have a much bigger cerebellum, relative to the size of their brain, than we have. The horse’s cerebellum is one third of the horse brain. Horses are wired for movement. Of course. They are prey animals. Running away is their defence.

The principle of proper mass tells us that horses have large parts of their brains dedicated to movement.

So, we know that horses have good capacity for learning and executing movement. This is one of the reasons we have used horses for so long. Horses have very good vision, particularly for light and dark, although they do not see colour like we do. Their vision in low light conditions is better than ours. Of course, we know that horses see a panorama of around 35 degrees. Horses hear higher frequencies than we do, but don’t hear as well as us at low frequencies. Horses are not especially good at determining where a sound is coming from compared with other mammals. Horses have a relatively large area of the brain dedicated to smell, and also to touch, so they are good at smelling and good at identifying things touching them.

Let’s look at some of the studies that have examined the sort of things that we would normally think of as smart. We know from research that horses can distinguish two apples from three apples, and prefer three, but can’t discriminate between four apples and six apples. Horses can recognise “larger” and “smaller”, with both two-dimensional and three-dimensional figures, open shapes versus filled-in shapes, and distinguish up to six categories — but there is a great deal of variability between individuals in this. Some horses can only distinguish two categories.

The “clever” horses can recall this learning six years later. Pretty impressive stuff. Generally, a horse’s attention span is short, around 10 seconds, but long-term memory and an ability to have a mental model of the landscape means wild horses can be quite systematic in their grazing of territory.

But I think the most interesting research that I have read is about a horse’s ability to read human emotion. A group of researchers, including Leanne Proops and Karen McComb in the UK, have shown a few interesting things. Horses preferred to approach humans with submissive body postures rather than dominant body postures (2018). Horses could discriminate between negative and positive human non-verbal vocalisations (2018). In other words, they could understand your tone of voice. Many of us know this, but now it has been demonstrated we should definitely be aware of it and make use of this. Soothe your horse with your voice, reprimand him with your voice before you do anything physical. He may come to understand quickly. (This has not been confirmed by scientific research, but is my opinion).

Research suggests horses can understand human emotion quite well.

Horses were able to discriminate human facial expressions on photographs, preferring happy faces to angry faces, and then several hours later, recognise the humans and demonstrate preference to the people of whom they had seen happy photos (2018). Wow!

This brings us to the really important area of feelings. We generally have two ways of “deciding” how to react to sensory information. We can use our frontal lobes to analyse and make a rational, logical decision to react to something. Or we can use deeper, phylogenetically older areas of our brain, called the limbic system, to use our feelings to organise our behaviour. We have feelings to drive action. Feelings are a fast way of responding to sensory information. For example, if the amygdala I mentioned before, the “smoke detector”, fires off and if we feel fear we are primed to run away; if we feel anger we fight.

We know that all mammals experience the same range of primary emotions that we do. A primary emotion is the automatic feeling that one has before you have thought about it and whatever it means. Happiness, sadness, anger and fear are all primary, but some others (Plutchik) include trust (acceptance), anticipation (interest), disgust and surprise. In 2015 the English group showed that they could reliably distinguish 15 facial expressions in horses, suggesting quite a complex emotional experience. Pain rating scales for horses have been developed looking at the facial expression of the horse.

The capacity of a horse to recognise and respond to a human’s emotion has been used in the development of specific schools of psychotherapy using horses. When you see horses responding to people who have experienced trauma in a therapy situation, it is really mind-opening. I have thought about this a lot and I do think that horses benefit from not having the impediment of frontal lobes that think and slow down reactions. Horse are just “in the moment” and will respond with innate and feeling-driven actions. Horses are social creatures and have been shown to be sensitive to other herd members. Horses have been domesticated for 6000 years. We have applied evolutionary pressure to develop horses that are sensitive to us. For example, even though a horse does not intrinsically know to follow a human hand that is pointing (in the way that a dog knows) a horse will easily learn to do this.

There is a lot of interest in the relationship between horse and humans, in fact, at the upcoming conference of the International Equitation Science Society, this is the main theme. It will be interesting to see what the academics have for us. I do think that what we know already suggests that horses are sentient. This will help us establish better ways to train and address adequate welfare. EQ